Rare Book Monthly

Articles - October - 2003 Issue

Book Lust and the Cultural Erotics of Fine Printing

By Megan Benton

A talk delivered to the Roxburghe Club, 16 September 2003

Copyright 2003

Near the end of the nineteenth century, American essayist and avid book collector Eugene Field published a book entitled The Love Affairs of a Bibliomaniac. In it he tells one tale after another, all with the same theme—that if forced to choose between a woman and a beloved book, a sensible man would be better off with the book. He even wryly speculates that if a woman works hard and behaves well, she just might be lucky enough to come back in another life as a book, “to be petted, fondled, beloved and cherished by some good man.” Clearly his tongue is in his cheek here, but the joke says more than Field maybe realized about his appraisal of the relative merits of women and books.

Quaintly bizarre as they may strike us today, Field’s attitudes were not unusual at the time. They are part of an unprecedented culture of book love, or bibliophilia, that flourished throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in both Europe and America. Bibliophiles formed a small but prominent international community of generally prosperous, genteel, and well-educated men. On the face of it, that they were all men is not surprising. Thanks to traditional advantages of wealth, leisure, and especially higher education—men had always been in a better position than women to develop and enjoy an affinity for books. Book ownership and literacy, particularly in the classical languages that signaled social and cultural rank, had always been a masculine enclave.

Those Victorian gentlemen were not shy about proclaiming their love for books. They wrote voluminously about their feelings, making two things clear. First, they declared book love strictly men-only territory. Women might love reading, they conceded, but only men could truly love books. British writer Holbrook Jackson put it bluntly: “it would be as easy to teach a cow to dance as even the average intelligent woman to love books as a man does. . . . Book love is as masculine . . . as growing a beard.” Second, bibliophiles expressed their passion in increasingly romantic, sensual, and even erotic terms. They seemed to be always—in their own words—fondling, caressing, stroking, and petting their books. French novelist Anatole France claimed that a true bibliophile’s hand cannot help but “voluptuously pass a tender palm over [a book’s] back, its sides, and its edges.” Bibliophiles frequently referred to books not as mere friends but as mistresses, sweethearts, darlings, even Delilahs. The rhetoric, and there’s a lot of it, is pretty hard to ignore.

Why? What prompted these men to go gaga over books? And why did it seem to be so strangely tangled up with sex and gender? Very roughly, the answers grow out of two major developments in the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution and the growing friction, even crisis, over women’s roles in society. Books and reading were intimately involved in both changes.

By the second half of the nineteenth century basic reading literacy levels approached 80-90 percent among adults in Western Europe and the US. An essential part of that rise was linked to a tremendous growth in the manufacture and distribution of books, spurred by industrialization. While a skilled printer with a hand press could produce about 250 impressions an hour, 8-10,000 or more soon flew from the jaws of mechanized, steam-powered presses. Even though books still weren’t cheap, and they were far outnumbered by magazines and newspapers, books were more accessible, to more people, than ever before. Thriving new chains of lending libraries only further ensured that almost anyone might read a book, anywhere, at any time. While this might sound great to folks like us, to many Victorians this sounded like social mayhem. Some feared the new readers—who were mainly women and the working classes—might be easy prey for ideas they wouldn’t understand properly. Others complained that their reading was a pointless distraction or worse, a waste of time better spent keeping the family, household, shops, and factories running smoothly.

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Botany.- Andrews (H.C.) <i>Coloured Engravings of Heaths,</i> 4 vol. in 2, first edition, [1710,--94]-1802-1809-[1830]. £10,000 - £15,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Botany.- Andrews (H.C.) <i>Coloured Engravings of Heaths,</i> 4 vol. in 2, first edition, [1710,--94]-1802-1809-[1830]. £10,000 - £15,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/c8ea395f-160f-48d0-8c6f-eb14b9c7bdf5.jpg)

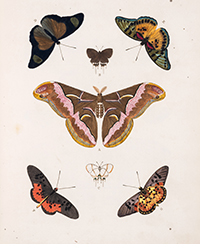

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Butterflies.- de Graaf (Willem Diederik Vincent). <i>[Inlandsche Kapellen in beeld],</i> 170 fine original watercolours, [Enkhuizen], [1800-40]. £8,000 - £12,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Butterflies.- de Graaf (Willem Diederik Vincent). <i>[Inlandsche Kapellen in beeld],</i> 170 fine original watercolours, [Enkhuizen], [1800-40]. £8,000 - £12,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/28c2fdc6-b72e-497e-9838-b2418859500f.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Zoology.- Felines.- Elliot (Daniel Giraud). <i>A Monograph of the Felidæ or Family of the Cats,</i> first edition, for the Subscribers, by the Author, [1878]-1883. £25,000 - £30,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Zoology.- Felines.- Elliot (Daniel Giraud). <i>A Monograph of the Felidæ or Family of the Cats,</i> first edition, for the Subscribers, by the Author, [1878]-1883. £25,000 - £30,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/74388261-9139-43c1-bb56-f1801a1d2175.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Birds.- Frisch (Johann Leonard). <i>Vorstellung der Vögel Deutschlandes,</i> 2 vol., first edition, Berlin, Friedr. Wilhelm Birnsteil, [1736]-1763. £40,000 - £60,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Birds.- Frisch (Johann Leonard). <i>Vorstellung der Vögel Deutschlandes,</i> 2 vol., first edition, Berlin, Friedr. Wilhelm Birnsteil, [1736]-1763. £40,000 - £60,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/7b144b2a-cde0-4b1f-be06-fa9568cf4aea.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Botany.- [Robin (Jean)]. <i>Histoire des Plantes, nouvellement trouvées en l'Isle Virgine…,</i>, 1620; with Geoffrey Linocier <i>L'Histoire des plantes,</i> second edition, 1619-20. £3,000 - £4,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Botany.- [Robin (Jean)]. <i>Histoire des Plantes, nouvellement trouvées en l'Isle Virgine…,</i>, 1620; with Geoffrey Linocier <i>L'Histoire des plantes,</i> second edition, 1619-20. £3,000 - £4,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a2a2dbe-8edf-4091-9a08-800f7aba747e.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Asia.- Japan.- Siebold (P.F. von). <i>Nippon. Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan,</i> 7 parts in 6 vol., first edition, Leyden, [1832]-1852. £35,000 - £45,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Asia.- Japan.- Siebold (P.F. von). <i>Nippon. Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan,</i> 7 parts in 6 vol., first edition, Leyden, [1832]-1852. £35,000 - £45,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9b1bf9d0-4e40-41d0-9957-d89a37e1313c.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Asia.- Valentijn (Francois). <i>Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën...,</i> 5 vol. in 8, first edition, Dordrecht [&] Amsterdam, 1724-26. £8,000 - £12,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Asia.- Valentijn (Francois). <i>Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën...,</i> 5 vol. in 8, first edition, Dordrecht [&] Amsterdam, 1724-26. £8,000 - £12,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/7ade0e81-f47b-45b3-bd2c-123a0469d82f.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Botany.- Australia.- Redouté (P.J.).- Ventenat (Étienne Pierre). <i>Jardin de la Malmaison,</i> 2 vol.,, Paris, 1803-04[-05]. £30,000 - £40,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Botany.- Australia.- Redouté (P.J.).- Ventenat (Étienne Pierre). <i>Jardin de la Malmaison,</i> 2 vol.,, Paris, 1803-04[-05]. £30,000 - £40,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0bc6575a-a6e5-44f6-8664-66fbad19c190.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [REGNART (LE LIVRE DE)]. <i>[Le] Docteur en malice, maistre Regnard, demonstrant les ruzes et cautelles qu'il use envers les personnes…</i> Rouen, 1550. €20,000 - €30,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [REGNART (LE LIVRE DE)]. <i>[Le] Docteur en malice, maistre Regnard, demonstrant les ruzes et cautelles qu'il use envers les personnes…</i> Rouen, 1550. €20,000 - €30,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/ddd3b34c-8abc-4eae-8474-6ea05406ccd0.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> TRITHÈME (JEAN). <i>Polygraphie et universelle escriture cabalistique.</i> Paris, [Benoît Prévost pour] Jacques Kerver, 1561. €8,000 - €10,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> TRITHÈME (JEAN). <i>Polygraphie et universelle escriture cabalistique.</i> Paris, [Benoît Prévost pour] Jacques Kerver, 1561. €8,000 - €10,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/cbc8d1a4-d991-48c7-b788-7554a6774b0e.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> VONTET (JACQUES). <i>L’Art de trancher la viande et toute sorte de fruits…</i> S.l.n.d. [probablement Lyon, vers 1647]. €20,000 - €30,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> VONTET (JACQUES). <i>L’Art de trancher la viande et toute sorte de fruits…</i> S.l.n.d. [probablement Lyon, vers 1647]. €20,000 - €30,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/21ad2e05-5544-44aa-887d-76df423e17af.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> HUGO (VICTOR). [Paysage spectral avec une église], [vers 1837]. €20,000 - €30,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> HUGO (VICTOR). [Paysage spectral avec une église], [vers 1837]. €20,000 - €30,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/dc734df9-0811-477f-919a-2563b8452855.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [HERVEY DE SAINT-DENYS (LÉON D')]. <i>Les Rêves et les Moyens de les diriger. Observations pratiques.</i> Paris, Amyot, 1867. €3,000 - €4,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [HERVEY DE SAINT-DENYS (LÉON D')]. <i>Les Rêves et les Moyens de les diriger. Observations pratiques.</i> Paris, Amyot, 1867. €3,000 - €4,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/7e769889-43a5-495e-a931-c511da576c2b.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> GACHET (PAUL-FERDINAND). <i>Les Chats de Gachet</i> (Manuscrit). S.d. [avant mai 1873]. €6,000 - €8,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> GACHET (PAUL-FERDINAND). <i>Les Chats de Gachet</i> (Manuscrit). S.d. [avant mai 1873]. €6,000 - €8,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/855dc2c0-17e3-4562-a1cc-2e7265c3769c.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [REDON (ODILON)]. PICARD (EDMOND). <i>Le Juré. Monodrame en cinq actes…</i> Bruxelles, Mme veuve Monnom, 1887. €7,000 - €9,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [REDON (ODILON)]. PICARD (EDMOND). <i>Le Juré. Monodrame en cinq actes…</i> Bruxelles, Mme veuve Monnom, 1887. €7,000 - €9,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/b325eb41-450b-4bd6-851c-4125e04dfbe7.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [TOULOUSE-LAUTREC (HENRI DE) ET HENRI-GABRIEL IBELS]. MONTORGUEIL (GEORGES). <i>Le Café-concert.</i> Paris, [1893]. €4,000 - €5,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [TOULOUSE-LAUTREC (HENRI DE) ET HENRI-GABRIEL IBELS]. MONTORGUEIL (GEORGES). <i>Le Café-concert.</i> Paris, [1893]. €4,000 - €5,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/6588f3a0-90f2-464c-8125-a76866eabe85.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [TERRY (EMILIO)]. <i>Projet de fontaine.</i> Dessin original au stylo et à l'encre noire. 1938. €2,000 - €3,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [TERRY (EMILIO)]. <i>Projet de fontaine.</i> Dessin original au stylo et à l'encre noire. 1938. €2,000 - €3,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0840c8e4-4f35-4c95-b2d3-3d5addd6fd51.jpg)