Rare Book Monthly

Articles - October - 2003 Issue

Book Lust and the Cultural Erotics of Fine Printing

Illustration from Sybil Grey, written anonymously and published by the American Tract Society in 1866

Just one example of such typographic virility is the fine edition of Leaves of Grass published in 1930 by Random House. The printers, Edwin and Robert Grabhorn, composed the book in an early Goudy typeface that, as Ed later explained, gave them "something the machine had discarded; . . . strong, vigorous, simple printing--printing like mountains, rocks and trees, but not like pansies, lilacs and valentines."

The type was printed with such force that it left deep sculptural impressions in the dampened handmade paper. Critic James Hart praised this heavy impression as part of the Grabhorns’ "strong masculine approach." As he put it, they didn’t “merely let the type kiss the paper lightly and discreetly but instead embedded it in a forceful embrace that could be felt by fingers as well as seen by eyes." The Grabhorns gave the book what Hart termed "integrity and virility."

Lurking throughout De Vinne's essay are references to the true culprit of printing’s feminization, the tyranny of consumers who prefer “fragile and useless types.” Printers foolishly defer to “false standards of light and delicate presswork,” he groused, and “waste their time over feminine composition that is unprofitable and highly distasteful to men of business. . . .” He resented that the sensible preferences of printers’ “best customers, . . . men of business,” had been ignored and even emasculated by the capitulation to female taste and style in book design.

A scene from the 1866 novel Sybil Grey depicts this social shift as well as the open, pale ordinary book design De Vinne scorned. The drawing depicts a bedridden man, unable to hold a book himself, being read to by his young daughter. With “delicate tact,” we are told, the child has stopped reading the material her father requested and shifted instead to “her dear little pocket-Bible.” The man is powerless to resist; decisions about what and how he reads are literally in the young girl’s hands. By contrast, conventions of domestic social reading in the 18th century dictated that a father, husband, or suitor would read aloud while the women listen. Don’t think it didn’t matter who held the book, who decided what would be read, when, where, and how.

But the greatest threat to traditional patriarchal book culture was not the new ascendancy of feminine tastes and values. Far more unsettling was the radical struggle of some women to move beyond those feminine circles. Throughout the century, women sought and occasionally gained new rights and freedoms; by the 1880s or so such ambitions had come to characterize the “New Woman.” Educated and economically self-sufficient, she scorned marriage and family to instead pursue intellectual, economic, and political equality with men. The world of books was one of the first to offer such opportunities, and growing numbers of women joined professional ranks of writers, editors, teachers, librarians. As New Women defined personal fulfillment in ways that did not need men in the traditional senses, many men feared not only for the social order but that manhood itself was in danger, both rejected and threatened by emboldened female appetites—political, cultural, literary, and finally, at heart, sexual. A popular cartoon of the 1840s suggests the perils to family life and manhood that many perceived when a woman picked up the pen with something to say.

Many Victorian men responded by reemphasizing clear categories for the sexes, stressing male and female as eternal opposites. The most famous Victorian gender model advocated “separate spheres,” allotting to men the competitive world of work, government, and business and to women the sheltering, nurturing world of home and family. At heart was the ancient gender dichotomy aligning men with qualities of mind—intellect, creativity, art, and culture—and associating women with the body—emotion, sensation, reproduction, and nature.

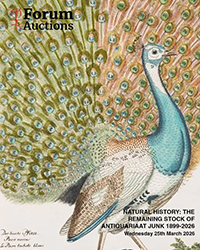

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Botany.- Andrews (H.C.) <i>Coloured Engravings of Heaths,</i> 4 vol. in 2, first edition, [1710,--94]-1802-1809-[1830]. £10,000 - £15,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Botany.- Andrews (H.C.) <i>Coloured Engravings of Heaths,</i> 4 vol. in 2, first edition, [1710,--94]-1802-1809-[1830]. £10,000 - £15,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/c8ea395f-160f-48d0-8c6f-eb14b9c7bdf5.jpg)

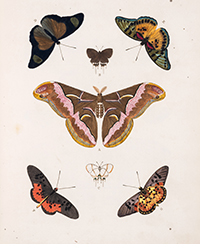

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Butterflies.- de Graaf (Willem Diederik Vincent). <i>[Inlandsche Kapellen in beeld],</i> 170 fine original watercolours, [Enkhuizen], [1800-40]. £8,000 - £12,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Butterflies.- de Graaf (Willem Diederik Vincent). <i>[Inlandsche Kapellen in beeld],</i> 170 fine original watercolours, [Enkhuizen], [1800-40]. £8,000 - £12,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/28c2fdc6-b72e-497e-9838-b2418859500f.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Zoology.- Felines.- Elliot (Daniel Giraud). <i>A Monograph of the Felidæ or Family of the Cats,</i> first edition, for the Subscribers, by the Author, [1878]-1883. £25,000 - £30,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Zoology.- Felines.- Elliot (Daniel Giraud). <i>A Monograph of the Felidæ or Family of the Cats,</i> first edition, for the Subscribers, by the Author, [1878]-1883. £25,000 - £30,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/74388261-9139-43c1-bb56-f1801a1d2175.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Birds.- Frisch (Johann Leonard). <i>Vorstellung der Vögel Deutschlandes,</i> 2 vol., first edition, Berlin, Friedr. Wilhelm Birnsteil, [1736]-1763. £40,000 - £60,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Birds.- Frisch (Johann Leonard). <i>Vorstellung der Vögel Deutschlandes,</i> 2 vol., first edition, Berlin, Friedr. Wilhelm Birnsteil, [1736]-1763. £40,000 - £60,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/7b144b2a-cde0-4b1f-be06-fa9568cf4aea.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Botany.- [Robin (Jean)]. <i>Histoire des Plantes, nouvellement trouvées en l'Isle Virgine…,</i>, 1620; with Geoffrey Linocier <i>L'Histoire des plantes,</i> second edition, 1619-20. £3,000 - £4,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Botany.- [Robin (Jean)]. <i>Histoire des Plantes, nouvellement trouvées en l'Isle Virgine…,</i>, 1620; with Geoffrey Linocier <i>L'Histoire des plantes,</i> second edition, 1619-20. £3,000 - £4,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a2a2dbe-8edf-4091-9a08-800f7aba747e.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Asia.- Japan.- Siebold (P.F. von). <i>Nippon. Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan,</i> 7 parts in 6 vol., first edition, Leyden, [1832]-1852. £35,000 - £45,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Asia.- Japan.- Siebold (P.F. von). <i>Nippon. Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan,</i> 7 parts in 6 vol., first edition, Leyden, [1832]-1852. £35,000 - £45,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9b1bf9d0-4e40-41d0-9957-d89a37e1313c.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Asia.- Valentijn (Francois). <i>Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën...,</i> 5 vol. in 8, first edition, Dordrecht [&] Amsterdam, 1724-26. £8,000 - £12,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Asia.- Valentijn (Francois). <i>Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën...,</i> 5 vol. in 8, first edition, Dordrecht [&] Amsterdam, 1724-26. £8,000 - £12,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/7ade0e81-f47b-45b3-bd2c-123a0469d82f.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Botany.- Australia.- Redouté (P.J.).- Ventenat (Étienne Pierre). <i>Jardin de la Malmaison,</i> 2 vol.,, Paris, 1803-04[-05]. £30,000 - £40,000. <b>Forum, Mar. 25:</b> Botany.- Australia.- Redouté (P.J.).- Ventenat (Étienne Pierre). <i>Jardin de la Malmaison,</i> 2 vol.,, Paris, 1803-04[-05]. £30,000 - £40,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0bc6575a-a6e5-44f6-8664-66fbad19c190.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [REGNART (LE LIVRE DE)]. <i>[Le] Docteur en malice, maistre Regnard, demonstrant les ruzes et cautelles qu'il use envers les personnes…</i> Rouen, 1550. €20,000 - €30,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [REGNART (LE LIVRE DE)]. <i>[Le] Docteur en malice, maistre Regnard, demonstrant les ruzes et cautelles qu'il use envers les personnes…</i> Rouen, 1550. €20,000 - €30,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/ddd3b34c-8abc-4eae-8474-6ea05406ccd0.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> TRITHÈME (JEAN). <i>Polygraphie et universelle escriture cabalistique.</i> Paris, [Benoît Prévost pour] Jacques Kerver, 1561. €8,000 - €10,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> TRITHÈME (JEAN). <i>Polygraphie et universelle escriture cabalistique.</i> Paris, [Benoît Prévost pour] Jacques Kerver, 1561. €8,000 - €10,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/cbc8d1a4-d991-48c7-b788-7554a6774b0e.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> VONTET (JACQUES). <i>L’Art de trancher la viande et toute sorte de fruits…</i> S.l.n.d. [probablement Lyon, vers 1647]. €20,000 - €30,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> VONTET (JACQUES). <i>L’Art de trancher la viande et toute sorte de fruits…</i> S.l.n.d. [probablement Lyon, vers 1647]. €20,000 - €30,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/21ad2e05-5544-44aa-887d-76df423e17af.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> HUGO (VICTOR). [Paysage spectral avec une église], [vers 1837]. €20,000 - €30,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> HUGO (VICTOR). [Paysage spectral avec une église], [vers 1837]. €20,000 - €30,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/dc734df9-0811-477f-919a-2563b8452855.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [HERVEY DE SAINT-DENYS (LÉON D')]. <i>Les Rêves et les Moyens de les diriger. Observations pratiques.</i> Paris, Amyot, 1867. €3,000 - €4,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [HERVEY DE SAINT-DENYS (LÉON D')]. <i>Les Rêves et les Moyens de les diriger. Observations pratiques.</i> Paris, Amyot, 1867. €3,000 - €4,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/7e769889-43a5-495e-a931-c511da576c2b.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> GACHET (PAUL-FERDINAND). <i>Les Chats de Gachet</i> (Manuscrit). S.d. [avant mai 1873]. €6,000 - €8,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> GACHET (PAUL-FERDINAND). <i>Les Chats de Gachet</i> (Manuscrit). S.d. [avant mai 1873]. €6,000 - €8,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/855dc2c0-17e3-4562-a1cc-2e7265c3769c.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [REDON (ODILON)]. PICARD (EDMOND). <i>Le Juré. Monodrame en cinq actes…</i> Bruxelles, Mme veuve Monnom, 1887. €7,000 - €9,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [REDON (ODILON)]. PICARD (EDMOND). <i>Le Juré. Monodrame en cinq actes…</i> Bruxelles, Mme veuve Monnom, 1887. €7,000 - €9,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/b325eb41-450b-4bd6-851c-4125e04dfbe7.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [TOULOUSE-LAUTREC (HENRI DE) ET HENRI-GABRIEL IBELS]. MONTORGUEIL (GEORGES). <i>Le Café-concert.</i> Paris, [1893]. €4,000 - €5,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [TOULOUSE-LAUTREC (HENRI DE) ET HENRI-GABRIEL IBELS]. MONTORGUEIL (GEORGES). <i>Le Café-concert.</i> Paris, [1893]. €4,000 - €5,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/6588f3a0-90f2-464c-8125-a76866eabe85.jpg)

![<b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [TERRY (EMILIO)]. <i>Projet de fontaine.</i> Dessin original au stylo et à l'encre noire. 1938. €2,000 - €3,000. <b>ALDE, Mar. 11:</b> [TERRY (EMILIO)]. <i>Projet de fontaine.</i> Dessin original au stylo et à l'encre noire. 1938. €2,000 - €3,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0840c8e4-4f35-4c95-b2d3-3d5addd6fd51.jpg)