It is a gigantic painting, displayed in the Louvre Museum, Paris. It has darkened over the years, which makes the scene it depicts even more dreadful: this is Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa. A book inspired it: Corréard’s true relation of the wreck of the frigate Medusa, off the African coast, in 1816. Out of 150 men thrown onto the infernal sea on a hastily-made raft, only 15 came back alive. Two centuries later, it remains as terrible a reading as ever.

Everyone French has heard of the raft of the Medusa, whose passengers were forced to eat human flesh to survive. Thus, laying my hand on a 1818 (second) edition of this testimony, I knew exactly what to expect. Well, not exactly. Leafing through the book, I casually read the first lines that my eyes came across, and they slapped me in the face: “The unfortunates who had escaped death during this terrible night turned to the dead bodies scattered all over the raft and cut them into slices (...) but many refused to touch them—including all of the officers. But since this dreadful food had revived those who had tasted it, it was suggested that we should dry it in order to make it more chewable. (...) Some tried to eat pieces of clothes, or the leather of their hats; but it led them nowhere. One sailor tried to eat his own faeces, but he could never do it.” Ladies and gentlemen, welcome aboard the raft of the Medusa!

The popular writer Cousin d’Avallon (1769-1840) wrote a relation of these events, which was published by Démoraine and Boucquin—the successors of Mr. Tiger, reads the title page (see article here). He writes: “We know that the French colonies of the West coast of Africa were captured by the English in 1808. They were given back to them by the Treaties of Paris in 1814 and 1815, and the Ministry of Marine set up an expedition of four ships bound for Senegal.” The Medusa was the command ship of the expedition, which counted 392 passengers, including civilians. Unfortunately, because of the incompetence of Captain Chaumareys (1763-1841), the Medusa hit the sandbank of Arguin, off Senegal, on July 12, 1816. The panic-struck officers built a raft in haste. 150 passengers were packed on board, including 129 soldiers and officers.

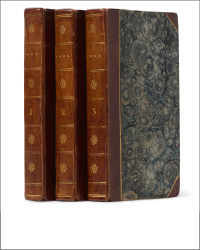

Our edition of Corréard’s book comes with an engraving representing the raft: “It was made of topmasts, yards, twines, (...) it was perfectly solid.” Yet, it was not very comfortable. “We were standing and we couldn’t move. We were all tightly packed (...). At the extremities of the raft, people had water up to their waists.” The first night was a stormy one and in the morning, “a dozen of unfortunates, who had been unable to take off their feet trapped in the gaps left between the various pieces of the raft, had drowned; several others had been taken away by the sea.” Forsaken by the rest of the expedition, many fell into despair, including two young ship’s boys and a baker, who “jumped overboard, after bidding farewell to their friends.”

The second night was a nightmare: “Mountains of water covered us restlessly and furiously broke among us. Those who stood at the rear and at the top of the raft were washed away; we all gathered at the centre, and those who could not reach there perished. We were so tightly packed together that a few of us died under the weight of their comrades who rolled over them every minute.” Out of the 75 persons who died this night, a quarter committed suicide. The following day, the stress and the pain triggered hallucinations, and “those who were not strong enough to fight them, inevitably perished.”

Géricault’s painting created a scandal when first displayed in 1818. The artist was even forced to modestly title it: Scene from a wreck—the political stakes were high. Indeed, as revealed in the introduction of Corréard’s book, the captain of the Medusa was to be blamed for such a disaster. His name was Chaumereys, and he was a poor sailor; but he had many acquaintances. And cowardice was added to incompetence, since he abandoned the raft without commandment, sailing away on a safety boat himself. When Corréard accused him in the first edition of his book, Chaumerey threatened to sue him. “Are we still living in a time when men and things are sacrificed to the whim of favour?” our author asks. Of course they were. Yet, Chaumarey had gone too far, and his guilt far too openly established. He was tried in 1818, relieved from his command and condemned to three years of prison. Indeed, the story took on incredible proportions in a society riddled with corruption and political resentment—the marine was said to be under the archaic control of the royalists, who ignored the recommendations of the Empire. In fact, the whole Restauration (in 1814, following Napoléon’s abdication the monarchy was restored until 1830) came under fire with this story.

This book became that powerful because it is shocking—in lesser proportions, it reminds us of Las Casas’ Destruction of the Indies. The very first relations such as the booklet of 8 pages printed at Sétier’s, Paris, in 1816, do not mention cannibalism. Géricault himself couldn’t represent it in his painting—that would have been far too provoking at the time; but after the publication of the full story by Corréard, it was on everyone’s mind. Man eating man to survive after being abandoned by those who were supposed to guide them? A political allegory of the time. But on the raft itself, it was everything but a parable. On the third day, “some wretches (...) turned to the dead bodies scattered all over the raft and cut them into slices; some devoured them right away.” The most educated ones—the officers, of course—allegedly first refused to eat “this sacrilegious meat.” But they eventually had no other choice; throwing some dead bodies into the sea, they spared one of them to eat it up.

The same day, a part of the passengers ran amok—so Corréard says: “They attacked us; we charged them, and the raft was soon covered with their dead bodies. Those of our adversaries who had no weapon tried to tear us with their teeth; several of us were badly bitten.” The fight came to a halt, after a while. But during the fourth night, “the Negroes convinced a handful of men that the land was near, and they decided to kill everyone on board. When he realized his plot had been unveiled, the leader (...) went to the top of the raft, enveloped himself in the sheet which he wore around his chest and jumped into the sea. His comrades rushed us to revenge his death. (...) With extraordinary effort, we repelled them again, and calm followed.” Thus, as the next day broke, “there were only 30 of us left.”

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)