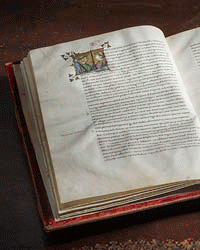

Le Tableau de Paris (Paris, 1782) is a crazy book written by Louis-Sébastien Mercier (www.rarebookhub.com/articles/2055). It describes Paris at the eve of the Révolution (1789). A few years later, Mercier hits the streets again—and portrayed Le Nouveau Paris, the new Paris! And it is... revolutionary.

Beheading A Capet

Reading Le Nouveau Paris (Paris, 1798) is like digging through a garage sale for treasures! It’s dusty, sometimes poorly written, and sometimes tedious—but full of hidden gems that will take your breath away. A member of the Convention, Mercier votes against the execution of Louis XVI (a historical blunder, he says), but he’s here the day “Louis the traitor” loses his head in Paris: “Could this be the same man, who was crowned at Reims as all the great men in his kingdom were kneeling before him? (...) Four knaves are shoving him on the scaffold, they’re stripping him, and his voice is being swallowed by the sound of the drum; tied to the plank of the guillotine, he’s struggling; and he receives the blade so badly that it doesn’t cut his neck, but his occiput and his mandible. His blood runs, (...) and all want to dip a finger, a feather or a piece of paper in it. One man tastes it, and shouts: so salty!” Mercier is hurt by what he sees, but he’s a convinced Republican, and has no regret: “We didn’t kill a man that day,” he says, “we killed a system.” He doesn’t feel sorry for the downgraded nobles or priests either—at one point, he urged the Convention to raze the castle of Versailles. Yet, he is a moderate—a humanist, and as such, a fierce opponent to barbarity.

The Man Who Almost Had My Head

A few years later, having escaped the guillotine himself, Mercier comes across the executioner Sanson (www.rarebookhub.com/articles/2309) in Paris: “A penny for his thoughts! He sleeps well at night, they say; and his conscience might be at peace. He comes and goes like anyone else, he goes to the show; he laughs, he looks at me; he almost had my head at one point, but he missed it; and he doesn’t care. I can’t help contemplating this man who’s sent so many people into the other world.” From April 1792 to August 1795, Charles-Henry Sanson beheaded 2,498 persons.

A Revolutionary Moustache

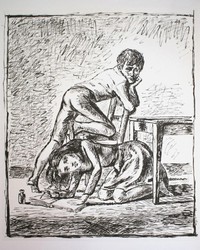

Princess de Lamballe, a Queen’s relative, is tried in 1792. As she’s about to hear her sentence, “several voices raised in the room, begging for mercy; there was a moment of general silence, and the murderers froze for a while—and suddenly hit her several times! She fell in a pool of her own blood, and they cut off her head, her breasts; her body was opened up, her heart was torn away; they stuck her head on a pike and they took it around Paris, dragging her body behind them. One of those monsters cut her genitals off, and wore them as a moustache.”

You’ll find hundreds of stories of that sort in this book: a father is incarcerated with his son by the revolutionary committee; he receives his order of execution and hastily walks to the guillotine without telling anybody—the executioner has mistaken him with his son, and he’s glad to die in his stead. The worst part? Mercier asks. Robespierre is arrested the same day, and everybody is released from prison. To make it short, I’ll quote F. Vanderem (Les Livres négligés): “It is historically impossible to understand certain aspects of the Révolution—characters, excesses, madness, everyday life, atmosphere—without reading Mercier.” I’d go even further, and I’d add that it’s easier to understand what the Révolution really means to a French citizen today if you haven’t read the following lines from Mercier: “It’s been 8 years since the great revolution has started—so many events! What a story! How old have we grown in such a short space of time! We’re about to celebrate July the 14th (when the Bastille was taken, the starting point of the Révolution), and our nephews are even more determined to celebrate such a glorious day. In the future, they shall reap the fruits of our pains. They will forget about our works, the dangers we’ve been through, they may even express unfair critics—just because they’ll never be able to figure out the torments we’ve endured; but whether they honour our memory or not, here’s one thing that will forever console me: I was born a subject, and I will die a Republican.”

The Fate of A Book

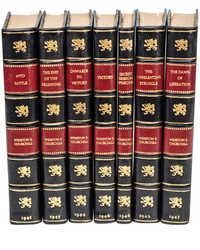

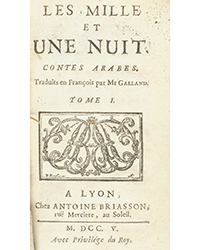

Le Tableau de Paris met with international success. In 2021, Olivier Ritz writes*: “According to Lüsebrink, Nohr and Reichardt’s statistics, Mercier was translated 58 times between 1770 and 1788—the most translated French author after Voltaire.” Le Nouveau Paris, first printed in Paris by Fuchs, Pougen and Cramer in 1798 (no date), was less successful. “Germany played a key role in its publication,” Olivier Ritz says. “The first edition was probably printed in Brunswick by Friedrich Vieweg, who put out a German translation almost concomitantly.” The “Brunswick edition” that also came out with no date would then be the true first edition. Although well advertised, it didn’t meet its public, neither in Berlin nor in Paris. The Opposition littéraire, a royalist publication, resented Mercier’s republican propaganda, and said the book wasn’t properly written. In 1801, Fortia de Piles anonymously wrote Six Lettres à S.L. Mercier (Paris, Year IX). The first lines of the introduction say it all: “I’ve read Le Nouveau Paris, and I found it full of ideas, often false, almost always incoherent, sometimes ridiculous or absurd—this is due to the fact that the author tries his best to appear new and original.” De Piles adds: “I didn’t use the first edition that came out a few months before the coup of Brumaire the 18th (November 9, 1799—so Le Nouveau Paris most likely came out in 1799); but the Brunswick edition of 1800, in six in-12° volumes, identical to the in-8° edition of Paris.”

According to the Rare Book Transaction History, a “very nice copy” of the “Paris edition” was sold for €875 by Alde, in Paris last year. A copy of the 1800 reprint mentioned by de Piles was sold for €488 by Alde, in Paris, in 2017. The “Brunswick edition” appears to be less frequent. As a matter of fact, a copy sold for €650 by Pierre Bergé & Associés in 2011, is described as follow: “First edition. Second issue, with a renewed title page.” Some copies of the “Paris edition” vary, though—volume IV of the “Paris edition” starts with: “ON lisait...”, while the Brunswick starts with: “On lisait...” for example.

Mercier’s new Paris went totally unnoticed until 1862, when two publishers reprinted it concomitantly. As Ritz puts it: “It stepped out into the light.” The great Baudelaire himself described it as “merveilleux” in a letter to his mother, and Victor Hugo borrowed a lot from it for his novel Quatrevingt-treize (1874). Yet Mercier is forgotten nowadays. The way he treats his subject, with multiple and mingled entries, blending topics, periods of time, and passing political judgements, is probably out of fashion. I think on the contrary that there’s no better way to teach history than turning dusty dates and events into lively scenes of flesh and blood. This book is an adventure—unplanned, unpredictable. Our ancestors were no “NPC” (non player characters)— they laughed, made love, cut each other throats and died under the sun, just like you and me. Do not ask for whom Guillotine’s blade shines, then—it shines for you and me.

Thibault Ehrengardt

* Un savoir littéraire sur la Révolution: le Nouveau Paris de Mercier. Rivista di Letterature moderne e comparate, 2021, LXXIV (2), pp. 145-155. hal-03872670

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> HAMILTON, Sir William (1730-1803) - Campi Phlegraei. Napoli: [Pietro Fabris], 1776, 1779. € 30.000 - 50.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> HAMILTON, Sir William (1730-1803) - Campi Phlegraei. Napoli: [Pietro Fabris], 1776, 1779. € 30.000 - 50.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0372eeb9-97e1-47b2-baca-b3287d4704ee.jpg)

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> [MORTIER] - BLAEU, Joannes (1596-1673) - Het Nieuw Stede Boek van Italie. Amsterdam: Pieter Mortier, 1704-1705. € 15.000 - 25.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> [MORTIER] - BLAEU, Joannes (1596-1673) - Het Nieuw Stede Boek van Italie. Amsterdam: Pieter Mortier, 1704-1705. € 15.000 - 25.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8f9ce440-b420-4407-8293-eb8e1b38ca19.jpg)

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> TULLIO D'ALBISOLA (1899-1971) - Bruno MUNARI (1907-1998) - L'Anguria lirica (lungo poema passionale). Roma e Savona: Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia, senza data [ma 1933?]. € 20.000 - 30.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> TULLIO D'ALBISOLA (1899-1971) - Bruno MUNARI (1907-1998) - L'Anguria lirica (lungo poema passionale). Roma e Savona: Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia, senza data [ma 1933?]. € 20.000 - 30.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/71bb9667-5d66-4aa8-96a2-9880c74a7a26.jpg)

![<b>Gros & Delettrez, Feb. 11:</b> DALVIMART, Octavien ou d’ALVIMAR(T)]. CLARK. The Military Costume of Turkey <b>Gros & Delettrez, Feb. 11:</b> DALVIMART, Octavien ou d’ALVIMAR(T)]. CLARK. The Military Costume of Turkey](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/ca2d66a9-721d-4878-a2eb-51a7bb9a3889.jpg)

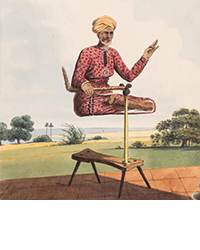

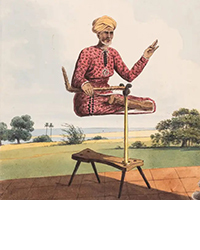

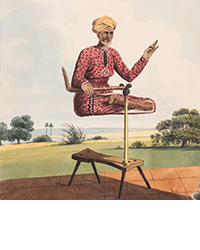

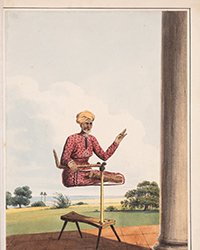

![<b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 57<br>[Album and Treatise on Hinduism], manuscript treatise on Hinduism in French, 31 watercolours of Hindu deities, Pondicherry, 1865. £3,000-4,000 <b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 57<br>[Album and Treatise on Hinduism], manuscript treatise on Hinduism in French, 31 watercolours of Hindu deities, Pondicherry, 1865. £3,000-4,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/f70b3790-9b4a-4990-b402-f0322021c0de.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 62 Allan (Capt. Alexander). <i>Views in the Mysore Country,</i>

[1794]. £2,000-3,000 <b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 62 Allan (Capt. Alexander). <i>Views in the Mysore Country,</i>

[1794]. £2,000-3,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/ad2cf7b4-4d93-4231-a956-b440583b39b3.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 123<br>D'Oyly (Charles). <i>Behar Amateur Lithographic Scrap Book,</i> lithographed throughout with title and 55 plates mounted on 43 paper leaves, [Patna], [1828]. £3,000-5,000 <b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 123<br>D'Oyly (Charles). <i>Behar Amateur Lithographic Scrap Book,</i> lithographed throughout with title and 55 plates mounted on 43 paper leaves, [Patna], [1828]. £3,000-5,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/5651043b-3c0d-4e2c-931f-72133bda9b36.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 205<br>Marshall (Sir John) and Alfred Foucher. <i>The Monuments of Sanchi,</i> 3 vol., first edition, 141 plates, most photogravure, [Calcutta], [1940]. £3,000-4,000 <b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 205<br>Marshall (Sir John) and Alfred Foucher. <i>The Monuments of Sanchi,</i> 3 vol., first edition, 141 plates, most photogravure, [Calcutta], [1940]. £3,000-4,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8c8244b7-4573-44d3-9c70-e0d3a3ed3cc4.jpg)