Antiquariat Kainbacher has released their Katalog XXII entitled Die Geschichte der Elektrizität Chronologisch aufgestellt von 1600-1850. That translates to “the history of electricity chronologically from 1600-1850.” Unsurprisingly, this catalogue is written in the German language. In 1600, little was known about electricity. The term was only first adopted at that time, and it was seen as something of an offshoot of magnetism, far more studied at this time. By 1850, it was well understood and its practical uses were now being developed. Here are a few of the electrifying items to be found in this catalogue.

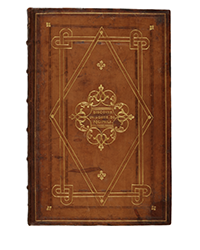

We begin with the first great English scientific work, De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure, by William Gilbert, published in 1600. Gilbert was a physician and natural philosopher whose studies were focused on magnetism. The translated title of his book is “on the magnet and magnetic bodies, and on the great magnet the earth.” Gilbert was also the first to employ the scientific method in England, commonplace today, to reach his conclusions. Gilbert concluded that the earth itself was a giant magnet, this explaining why a compass works. Along the way, Gilbert discovered another attractive force, which he realized was not the same as magnetism. He found it from using amber, so he named it after the Greek word for amber, electric. Today we call it static electricity.

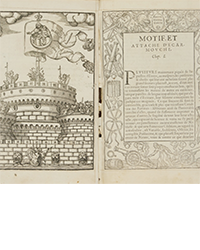

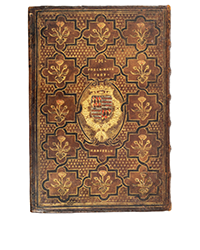

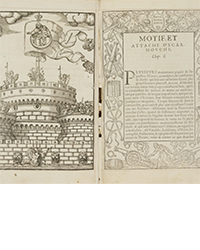

Athanasius Kircher has been described as the “last Renaissance man.” Perhaps knowledge was becoming too great by the middle of the 17th century for anyone to be knowledgeable in every field imaginable, but Kircher was such a man. He also wrote about everything and his theories tend to be a cross between science and the fantastical. He studied volcanoes, only to describe imaginary worlds that existed below the eruptions. Here is his book on magnetism, Magnes sive de arte magnetica opus tripartitum quo universa magnetis... the third, last, folio, and best edition, published in 1654. Kainbacher describes the book as an “encyclopedic work on magnetism,” “a collection of scientific and fantastic theories.” The Jesuit scholar describes his invention to measure magnetic force and applied it to fields such as geography, electricity, and astronomy, but also wanders into fields we think of as “animal magnetism,” its affect on animals, music and love. That isn't the type of magnetism we associate with magnets.

Jean Antoine Nollet was a major figure in the research of electricity in the middle of the 18th century. A French scientist, he is credited with popularizing the study of this still little understood phenomenon. He presents his theories in Recherches sur les Causes Particulieres des Phénoménes Électriques, this being a third edition published in 1753. Nollet developed the double flow theory of electricity. He believed it was a fluid that could penetrate even dense bodies through pores. There were affluence and effluence pores through which it flowed in and out. Unfortunately for Nollet, Benjamin Franklin was undertaking his experiments in electricity over in America at this time and he reached very different conclusions. Nollet stubbornly stuck to his beliefs even as the scientific community moved in Franklin's direction.

Speaking of Mr. Franklin, he began publishing on the subject of electricity in 1751. His findings were put together in this book, Experiments and Observations on Electricity made at Philadelphia in America. This is a fourth and first collected edition of Benjamin Franklin's observations, the first to include his notes and correspondence. It was published in 1769. Printing and the Mind of Man describes it as “the most important scientific book of 18th century America.” It includes Franklin's famous kite and key experiment where he proved that lightening was electricity, and that this was something different than simple static electricity. Franklin is remembered today in America mostly for his political achievements but in the days before the Revolution, his reputation was primarily that of a scientist.

The electrical unit the volt is named after this man, Alexander Volta. Volta was a turn of the 19th century Italian physicist who improved on the theories regarding electricity of his countryman Luigi Galvani. Galvani had done the famous jumping frog legs demonstration of an electrical current, but thought it was something in the animal. Volta realized it was simply a chemical reaction. This enabled Volta to develop the first true battery, creating electrical power from a chemical reaction. Offered is Collezione dell´Opere del Cavaliere Conte Alessandro Volta, a five-volume collection of Volta's work published in 1816.

Antiquariat Kainbacher can be reached at 0043-(0)699-110 19 221 or kainbacher@kabsi.at. Their website is found at www.antiquariat-kainbacher.at.

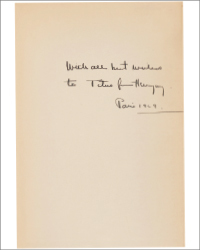

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)

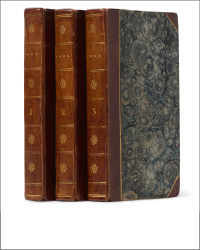

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)