In 1770, the atheist Philosopher Paul Henri Thiry, baron d’Holbach (1723-1789), revisited the history of Jesus Christ in his book Histoire critique de la vie de Jésus-Christ/A Critical History Of Jesus-Christ. Casting the light of reason over the New Testament, he challenged its infallibility, trying to free mankind from the devilish hold of the Church of Rome.

Remember! The Earth was, according to the holy and infallible Bible, only 5,748 years old, and the multitude lived their lives according to the rules set by the priests. Should someone point out a contradiction or inconsistency in the Book, they were told that God moves in mysterious ways. “In the name of these mysteries are we told to respect religion and those who teach it,” Holbach writes in Histoire Critique de Jésus-Christ. “Consequently, we may assume that the obscurity they contain was placed there on purpose.” He was one of those French Philosophers of the 18th century who considered that the Church had kept people in ignorance to maintain its earthly power—and decided to put an end to it.

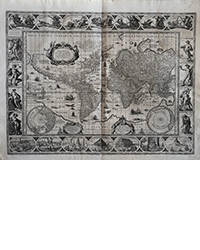

Voltaire spearheaded this anticlerical movement, but he did it with—humour—some sort of restraint. Underlining some obvious mistakes in the Bible (the discovery of the New World was the first blow to its infallibility) made obvious by the progress of science, he concluded: “This is not a problem should we consider that God sent the Bible to make better Christians out of us—and not better geographers.” Voltaire fought against the Church, but not against religion, “the holy link of society.” His Epistle to Uranie (1732), which is reproduced at the opening of Holbach’s book, ends up on the lines: “He (God) judges us on our virtues, not on our sacrifices”—in both cases, He judges us. Voltaire was a deist— Holbach was an atheist: “Everything in (the Bible) is but disorder, obscurity, and barbarity of style—as if purposely trying to disconcert the ignorant, and disgust the learnt.” He doesn’t question the miracles of Jesus only, but the New Testament on a whole: “Four ignorant and illiterate men are the supposed authors of the theses memoirs (...). Nothing of all this has ever happened! The Gospels tell an Oriental tale that will disgust men of good sense. It was meant for ignorant and stupid people—the rabble; they are the only ones they can lure.” Cursed are the meek.

Fiat lux!

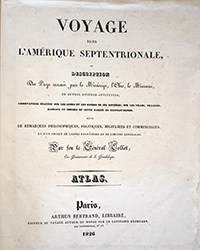

Holbach’s book “miraculously” came out: no date (circa 1770) and no author’s name—an immaculate conception, and a wise precaution. It has since been credited to Holbach by Barbier (Dictionnaire des ouvrages anonymes—Paris, 1874; tome 2, p647), and although condemned by censorship, it was reprinted in 1778 (fake address in Amsterdam). Holbach calling himself “an incredulous,” was “no victim of holy blindness.” Thus he went on the mountaintop and here is what his eyes beheld!

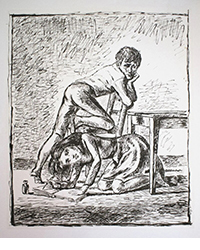

One day, the Archangel Gabriel came to Mary. Actually, it was most likely “a lover, who, making profit of Joseph’s absence, found a way to declare and satisfy his passion.” Joseph, her husband, flew into a rage upon finding out she had cheated on him, and probably threatened her with reprisals. She was thus forced to fly to Egypt with “his putative child”. There, the young Jesus learnt “a bit of medicine and a few things about spasmodic diseases of women—enough for the vulgar to see him as a sorcerer or a miracle maker.”

Did he learn a few tricks as well? Holbach suspects so. After 30 idle years, Jesus decided to preach, and turned to his cousin John, who was already baptizing people on the bank of the Jordan River. He went to “confer with him—or, if you want, to get baptized”, and they shared the roles. When John was arrested, “the Messiah*, fearing that his predecessor’s problems might get to him (...) went to hide in the desert, where he remained for 40 days.” Through a series of dubious miracles—“miracles cost Jesus nothing when they were planned beforehand, but he never made any improvised one, nor in the presence of people he considered as too clever.”—, Jesus soon gathered a “large crowd of lazy people” who suffered from “very convenient stupidity.” From the donations he required from his new disciples, he sometimes unexpectedly fed the multitude that was starving (the miracle of the loaves); other times, benefiting from circumstances, he gave the impression of walking on water.

Jesus met with what Holbach calls a legitimate resistance from the Jews, as he was openly challenging their laws and traditions. Furthermore, he was a “vindictive and turbulent man”; rejected by the Jews, he turned to the Gentiles. But he was losing ground. “At the end of his mission, the crowd doesn’t follow Jesus (...) In last resort, he tried to attract the Publicans, and the clerks, who were highly despised; they were but a weak support, and their company cost Jesus the sympathy of his last supporters.” He then decided to bring back Lazarus to life. But this miracle was one too many—Lazarus and Jesus were long-time friends and “the Jews felt so much malice that, far from converting, they seized the occasion to take serious measures against Jesus.” The messiah then went to Jerusalem on a donkey, “out of humility or because he had no choice”, to preach. His last attempt at rallying the Jews was a failure. “Our hero often loses his mind; his character is a mix of boldness and pusillanimity. Accustomed to shine in front of the vulgar, he didn’t know how to behave in front of vigilant and learnt enemies.” He was betrayed, arrested and the rest is... history? “I remain convinced,” Holbach concludes, “that this man may have been a fanatic, who genuinely thought he was inspired and sent by God to lead his nation—in a word, a messiah; and that he didn’t mind, in order to succeed, using the most efficient frauds to convince a people that would have never listened to him hadn’t it been for miracles.”

A modern reader left a comment on a platform about the recent reprint of this book: “Useless,” he wrote. “Our modern biblical scholars have found so much more relevant things in-between!” But you shall not judge a book by its contents only—the date it was published is of high importance! When the Earth was not even 6,000, it was quite courageous and bold to write such a reasonable book. Furthermore, there’s something exciting about Holbach’s vision of Jesus, especially from our modern point of view. Was Jesus an ordinary yet extremely intelligent man carried away by heavenly visions, passionately feeling the presence of God within? Did Christianity spring from built-up miracles and pious stupidity? Maybe, but at the end of the day, does it really matter? Could reason ever prevail in Man’s life? Man was created unreasonable, and he will always lend a keen ear to the good ole snake. Of course, France has overtaken religion, and chased it away from the core of its institutions. But in certain places where the Church still influences hundreds of thousands of lives, the question of the infallibility of the Bible remains—in this regard, Holbach’s book seems to be a reasonable enough read.

* Holbach objects: Jesus couldn’t be from the Tribe of David as required from the messiah if John’s mother, Elizabeth, was Mary’s relative. Indeed, Elizabeth was married to a priest (as the Bible reads), meaning she was, like her entire family (including Mary then Jesus), from the tribe of Levy.

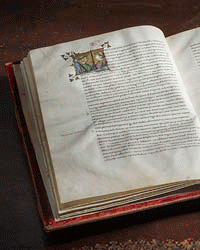

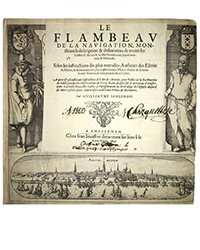

- Histoire critique de Jésus-Christ, ou Analyse raisonnée des Evangiles (no place, no date—1770). Title page / Epistle (III to VIII) / Preface (XXXII pages) / 398 pages / 2 pages.

![Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:

HAMILTON, Sir William (1730-1803) - Campi Phlegraei. Napoli: [Pietro Fabris], 1776, 1779. € 30.000 - 50.000 Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:

HAMILTON, Sir William (1730-1803) - Campi Phlegraei. Napoli: [Pietro Fabris], 1776, 1779. € 30.000 - 50.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0372eeb9-97e1-47b2-baca-b3287d4704ee.jpg)

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> [MORTIER] - BLAEU, Joannes (1596-1673) - Het Nieuw Stede Boek van Italie. Amsterdam: Pieter Mortier, 1704-1705. € 15.000 - 25.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> [MORTIER] - BLAEU, Joannes (1596-1673) - Het Nieuw Stede Boek van Italie. Amsterdam: Pieter Mortier, 1704-1705. € 15.000 - 25.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8f9ce440-b420-4407-8293-eb8e1b38ca19.jpg)

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> TULLIO D'ALBISOLA (1899-1971) - Bruno MUNARI (1907-1998) - L'Anguria lirica (lungo poema passionale). Roma e Savona: Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia, senza data [ma 1933?]. € 20.000 - 30.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> TULLIO D'ALBISOLA (1899-1971) - Bruno MUNARI (1907-1998) - L'Anguria lirica (lungo poema passionale). Roma e Savona: Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia, senza data [ma 1933?]. € 20.000 - 30.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/71bb9667-5d66-4aa8-96a2-9880c74a7a26.jpg)