Editor's Note: This is part II of a series begun in the August issue of Rare Book Monthly.

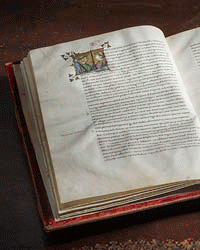

Welcome back to the dark and smelly streets of the French capital in the 18th century, with the same guide, Mercier’s second edition of Tableau de Paris (Amsterdam, 1782)—but with a different focus. Let's talk about what really matters, books when they were not old yet.

Paris was, according to our guide, the city in the world where you could find “the most books”. But the vast majority of them, he says, were insignificant and “the only good—and consequently prohibited—ones” were not to be found at official booksellers’ but with the peddlers. Thus, the “mouchards” (informers) constantly harassed these itinerant salesmen, who, being illiterate, had no clue about what they were selling. “They would hide the Bible under their coats should the lieutenant of police ban it”, underlines Mercier. When caught, they were sent to the Bastille, or exposed to popular anger in yokes. But this illegal trade was in fact “orchestrated by police officers”, who picked up their own dealers, thus “earning more than thirty peddlers together!” Corruption and hypocrisy were at their peak, especially in the Gazettes (newspapers), which were filled with “official lies”. Yet, you could see dozens of people sitting in public places, avidly reading them. It had become so hard to find a honest book printed in France that “people abroad have lost all consideration for our books”, laments Mercier. “The barriers raised against free speech have deteriorated the quality of even entertaining books.” Thus, coming across a book printed “with privilege”, Mercier knew “that it contains nothing but political lies.” Let’s remember that his own book was published in Amsterdam, and that the government persecuted him after its first publication—he went abroad to put together the second edition because some details about Paris had offended the police of books.

The “royal censors” were responsible for what they authorized to be published, and so they took no chance. “Worried and pernickety to the excess, they end up approving insignificant works only.” Censorship and the fear of consequences led to absurd situations such as a theologian from La Sorbonne attesting: “Nothing hurts the Christian faith”... on the front page of the Coran. Meanwhile, the good manuscripts surreptitiously left France to make the Dutch or Swiss printers rich.

Painfully learning Latin

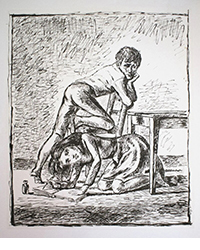

Illiteracy was galloping in Paris. And learning how to read and write could be quite painful. In the “petites écoles” (elementary schools), physical abuse was common practice. “There you can see tears running down the cheeks of our children, you can hear them moaning, as if pain was made for kids and not for grown-ups. Some teachers, whose mere sight frightens us, mistreat the first age of life.” Providing they were Catholics, these brutes could “be rude and tough, and beat innocent creatures in the name of Jesus Christ.” Contrary to what most people think nowadays, people who could read Latin were few at the time—a good education was a rich man's privilege. The language of prestige, it was used for the inscriptions on public monuments. “What? Not a thought for common people? A water carrier, while filling up his bucket at the fountain, will forever gaze in wonder at two verses in Latin he can’t decipher? His own country refuses to communicate with him, even at the fountain!”

Many “bourgeois” sent their kids to college, so they could learn Latin. But it only filled their heads with unrealistic aspirations, driving them to idleness and desperation, says Mercier. Looks like Latin had already started to become “useless” in 1782! Yet, best selling books were written in Latin. Of course, they were religious books. The breviaries sold up to 20 or 30,000 copies! “Famous authors, can you say the same?” asks Mercier. Even the priests could hardly read Latin fluently, yet they bought breviaries in four “gilt-edged” volumes, before “casually leaving one volume on their mantel—and the booksellers ask for no more, as they make fortunes with these works in Latin that sell more than those of Voltaire or Rousseau.” These books were a source of pride, and consequently of ridicule in Paris. “A devout old lady has a copy of the Euchologue magnificently bound, and has it triumphantly carried to the church by her lackey; she wants everyone to behold the golden binding.” Meanwhile, the priests walked the streets displaying a breviary under their arm, moving their lips as if silently reciting it, and staring at the skies in bliss. But laughter was the most efficient weapon against bigotry, and “ever since we’ve started laughing at it, the habit of praying in public has almost disappeared.”

From Scratch

All day long, the “chiffoniers” of Paris roamed the streets, picking up torn pieces of rag on the dirty pavement with their hooks. “Have I just uttered the vile name of chiffonier?” Mercier asks. “Do not look away, this material will become the ornament of your book shelves, and the precious treasure of humanity. Our “chiffoniers” lead the way for Montesquieu, Buffon and Rousseau.” All these rags were indeed turned into paste, and then into the paper upon which the most brilliant ideas could claim for eternity. “Blessed be the chiffoniers!” triumphs Mercier, unaware that most of us would be sniffing this smelly and thick paper more than 200 years later!

Of course, the most valuable works were not the most sought-after. If you asked a “book renter” the works of the famous author La Harpe, he would beg your pardon before sending you to a luthier, mistaking the “harp” with “la Harpe”. He only sold “torn and dirty books”, which thereby proved their popularity. The disdainful critics should visit the book renters to have a look at what people really like, suggests Mercier; so should the writers, to make sure their works were there available—“and if they are not, or if the copies of your books are too neat, just tell yourself: I have too much talent, or not enough.” These books were not for sale, but for rent - for a day or two. Some were so fashionable that the renter had to split them in two or three to satisfy the demand, renting each part separately and by the hour! These book renters knew nothing of their books but their backs—just like most librarians, says Mercier, and a few princes, whose book collection was usually more useful to others than to themselves. What kind of books did they rent? “The naive and sincere ones, those deprived of all haughtiness and academic jargon”—the ancestors of sitcoms, so to speak.

Needless to say, you hardly came across a torn copy of the Almanach des Muses there. This compilation of poems (usually bound in full morocco, they are quite valued by collectors today) came out once a year, in January. The compiler begged the authors for their work all year long, and was consequently called “the mendicant friar”. He was somewhat making a bouquet of flowers, except that he did not care much about the coordination of colours or scents; he mingled them together with no taste, just caring about the size of his final bouquet. People commonly offered a copy of the Almanac to their friends during the first two weeks of the year—and forget about it.

Poor Rousseau

A literary—and to some extent, a philosophical—war then opposed the two main pillars of French philosophy, Voltaire and Rousseau; and Mercier clearly sided with the latter. Though preaching social progress, Mercier didn't like the “sect of the encyclopaedists” led by Voltaire, whom he described as a “prisoner of pride.” A living legend, the “author of La Pucelle” had left Paris years ago to live at Ferney, far from censorship and his enemies. But just before he died in 1778, he came back in triumph to Paris—Mercier talks about “the triumph of Voltaire”, and he says it was orchestrated by the notorious “sect of the encyclopaedists.” During the ceremony, the “dwarfs of literature came to meet him, saying: “You’ve praised my work!” But the old man had forgotten about their names and the certificates of immortality he had delivered them - he had never spared with those.” But the many visits he received soon exhausted him, and his life was “shortened by his dear friends—the apotheosis killed the poet.” Mercier adds: “Ever since the triumph of Voltaire, the sect of the encyclopaedists has been in a shaky state; what will become of it?”

Well, the true triumph of this “sect” was yet to come—it was later called the Révolution (1789). Mercier didn’t know about it, of course. But as Voltaire and Rousseau were rivals, so were many of their respective admirers. Mercier once went to visit his hero, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in Rue Plâtrière, Paris—“the most noisy and uncomfortable street of Paris, and the one with the most bad places.” But Mercier was soon overwhelmed with sadness: “How painful it was to realize that the author of Emile had become mentally sick! I sighed when he told me about his alleged enemies, of the universal conspiracy set against him. I was saying to myself: “What? The man I’ve so much admired is now a maniac?” Indeed, at the end of his life, Rousseau thought he was followed in the streets, that people all over Europe were spying on him, and wishing him evil—from the King of Prussia to the nearby vegetable vendor. This portrait of Rousseau, lost both in his madness and in the middle of the dirty city of Paris seems to sum up the painting of Paris drawn by Mercier—wild, intensive, scary at times but always fascinating. It's just like hearing the faded murmurs of “our brothers who lived before us”, and who, God bless them, wrote and printed many books.

T. Ehrengardt

The book: No name (Louis-Sébastien Mercier). Tableau de Paris (Amsterdam, 1782). Four in-8° volumes. The first edition came out anonymously in two in-8° volumes (Neuchatel, chez Samuel Fauche), in 1781. The printer was arrested by the police of books but refused to give away the name of the author, who apparently surrendered to the police. He then went to Switzerland in order to put the second edition together. Tableau de Paris has become a classic, and it later came as a twelve in-8° volumes between 1782 and 1788 (Amsterdam).

![Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:

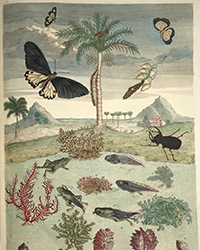

HAMILTON, Sir William (1730-1803) - Campi Phlegraei. Napoli: [Pietro Fabris], 1776, 1779. € 30.000 - 50.000 Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:

HAMILTON, Sir William (1730-1803) - Campi Phlegraei. Napoli: [Pietro Fabris], 1776, 1779. € 30.000 - 50.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0372eeb9-97e1-47b2-baca-b3287d4704ee.jpg)

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> [MORTIER] - BLAEU, Joannes (1596-1673) - Het Nieuw Stede Boek van Italie. Amsterdam: Pieter Mortier, 1704-1705. € 15.000 - 25.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> [MORTIER] - BLAEU, Joannes (1596-1673) - Het Nieuw Stede Boek van Italie. Amsterdam: Pieter Mortier, 1704-1705. € 15.000 - 25.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8f9ce440-b420-4407-8293-eb8e1b38ca19.jpg)

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> TULLIO D'ALBISOLA (1899-1971) - Bruno MUNARI (1907-1998) - L'Anguria lirica (lungo poema passionale). Roma e Savona: Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia, senza data [ma 1933?]. € 20.000 - 30.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> TULLIO D'ALBISOLA (1899-1971) - Bruno MUNARI (1907-1998) - L'Anguria lirica (lungo poema passionale). Roma e Savona: Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia, senza data [ma 1933?]. € 20.000 - 30.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/71bb9667-5d66-4aa8-96a2-9880c74a7a26.jpg)