Cartouche’s skull, the ultimate trick?

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

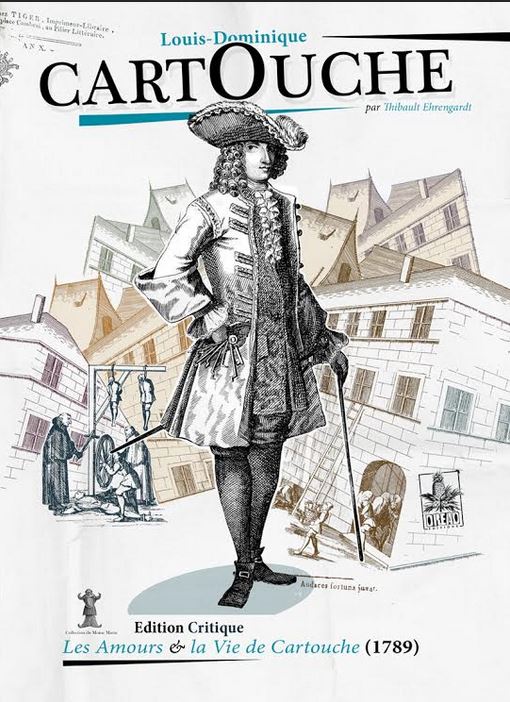

Reprint of the faked Loves and Life of Cartouche.

The Russian anthropologists

The Cartouche mystery obsesses even the Russian anthropologists, who recently carried out a facial reconstruction, using the skull of the Musuem. The two drawings of their work, a front view and a profile view, show a sad face with a regular jaw and some recesses on the temples. “These drawings prove nothing, if you ask me,” stated Mr Mennecier. Indeed, this is but another blurry indication in Cartouche’s physical misrepresentation. The portrait added to the peddling editions of his Life (which sold by hundred of thousands until the mid-19th century), for instance, created some confusion—this book cared about nothing but selling paper, and didn’t pay much attention to historical truth. On the portrait, Cartouche even wears a shirt à la Louis XVI. While imprisoned in Le Châtelet, though, Cartouche had many visitors, including several painters. The only contemporary engraving to be found shows Cartouche in chains, and sitting on a stony bench—in Causes Célèbres (Paris, 1859). Armand Fouquier describes it as quite realistic: “The kid it represents, with his sly expression, his pug nose, his wide mouth, high cheekbones, slanting eyes, his narrow forehead, does fit with the shape of the skull—a half-monkish and half-doggish skull.” Let’s ignore the assimilation to dogs and monkeys, the days of physiognomy are—thank God—over; unfortunately, Mr Fouquier doesn’t say where he saw the skull. Apparently, it was shown with the one of Descartes during the 19th century at the Museum of Natural History. But another engraving challenges the accuracy of the above-mentioned one; it was published in 1755, and represents the infamous bandit Louis Mandrin at the eve of his execution. Except the face itself, and a scene of execution added to the background, it is the exact copy of Cartouche’s. The faces might have been modified, it still tells a lot about the liberty taken by painters and publishers at the time. We also know that Meunier Callac sold several painters the right to draw the portrait of Cartouche at Saint Côme, but it looks like none of these precious documents ever reached us.

A wax bust

There’s also a wax bust of Cartouche, kept in the closed Museum of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. It was allegedly moulded directly on Cartouche while he was still alive—on the Regent’s orders. “Tradition has it that the hair and the moustache,” wrote the curator of the Museum in 1837, “were cut from the corpse and then placed on the bust.” This peculiar testimony, once showed at Desnoue’s—a Parisian antique dealer—, has been kept away from the general public since 1979. Anyway, Armand Fouquier, who had a lot of certainties, wasn’t convinced by this bust: “You just have to look at the Scaramouche type of the face which skeletal structure has nothing in common with the truly authentic skull of Cartouche (...) to realize that this is nothing but a toy of the time, that reminds the silly Cartouche painted by the second-class playwrights.” But what if the Museum’s skull isn’t the authentic skull of Cartouche, but the one of a 14th century rebel? There’s one way to find out: a mere carbon dating. It would cost 500 euros. Are we standing a handful of euros far from the truth? Not quite sure—as stated by Mr Mennecier, there’s a margin of error of 200 years, which makes the dating quite uncertain. Back to mystery, then—where the life and death of Louis-Dominique Cartouche seem to belong.