Francisco Lopez de Gomara, or the Certain Curse of an Uncertain Translation

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

St. Paul and the snake.

One of the best books on the conquest of the New World, Francisco Lopez de Gomara’s Historia general de las Indias (1552), raised controversy when it came out in France in 1569—mainly because the French translator turned a “maybe” into a “certainly”, thus unveiling a crucial theological issue.

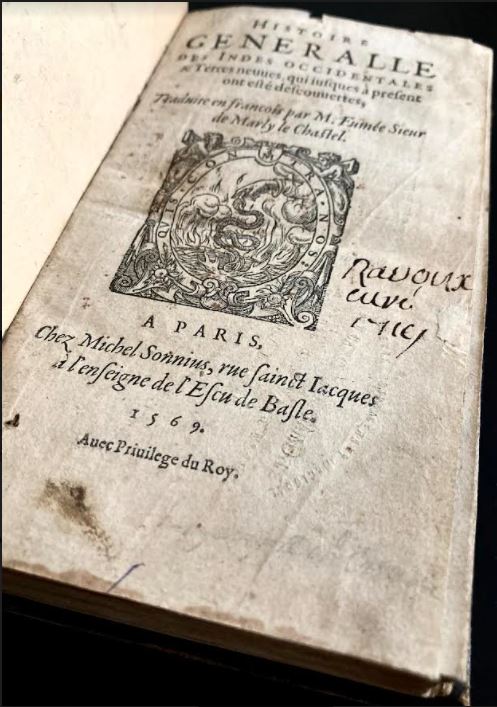

Gomara (1511-1559) never set a foot in the New World, but he had access to first-hand sources and talked to several famous conquistadores. Consequently, his Historia de las Indias was a success. It was soon published abroad; first in Italy, then in France by Michel Sonnius, in 1569. Sonnius graced the front page of the first edition with his gorgeous label, which represents a snake biting Saint Paul’s finger above a fire. Quis Contra Nos, the motto asks—who shall be against us? No one, si deus pro nobis—if God is with us. The drawing is a reference to the apostle being bitten by a viper. “But Paul shook the snake off into the fire and suffered no ill effects.” (Acts 18:5). The title page also reads: Translated into French by M. Fumée. “Fumée translated Gomara’s works in two parts,” Matthieu Gerbault writes*. “The first one in 1568 (...), and the second one (the conquest of Mexico) in 1584. (...) A thorough analysis of his turns of phrase and of the way he translated names indicates that he didn’t work from Gomara’s Spanish text but from Cravaliz’ Italian translation, which is quite faithful to the original.” At the time, France was going through the terrible wars of religion that opposed the Catholics to the Protestants, and America was of little interest to them. As a matter of fact, it was regarded as a vulgar topic. In the preface, Fumée explains that he translated Gomara’s book only “to relieve (his) grieved mind in such calamitous times.” But we shall see that crucial issues were at stake.

Reading Gomara in a 1569 edition is a once in a lifetime experience. This is not “old French”, but this is not “modern French” either—this is actually “middle French”. The obsolete spelling of bizarre words, the destabilizing turns of phrase and the general “tour d’esprit” of such a book create a delicious, and not impassable, barrier that adds to the reader’s pleasure. What could be more exciting than to be plunged into a new world of words when reading about the discovery of a new world? And Gomara’s relation ranks among the best. “From Léry to Montaigne to La Popelinière to Luc de La Porte, many writers stole colourful details from Gomara,” Gerbault states. “Even Thevet, who despised Gomara because he had never been to the West Indies, had no problem with plagiarizing several passages of Historia general de las Indias.” We know that Montaigne also used it as a source for his Essays.

Although Gomara doesn’t omit to mention the conquistadores’ brutal deeds, he mostly praises them for their courage and boldness. But Las Casas’ horrifying relation of their bestial behaviour was on everyone’s mind. The “black legend” of Spain was spreading in Europe, especially since other nations were denied access to the riches of the New World. A particular passage of the book outraged the virtuous readers. In Chapter 218 of the French translation—the original relation has no chapter—, Gomara talks about the Native Americans: “I firmly believe that God has doomed those poor wretches to servitude only to punish them for being wicked. Indeed, I do think that Ham has not sinned against his father Noah as much as those Indians have offended God; therefore I assume that they are Ham’s descendants, and that they have inherited from him the malediction of God.”

A French Protestant preacher named Urbain Chauveton publicly criticized this passage along with several others, which he said were trying to justify the enslavement and brutal slaughter of the Native Americans. “But Chauveton’s quotes were not accurate,” Gerbault writes. “That’s because he was referring to Fumée’s unfaithful translation.” In 1588, one Le Breton decided to put an end to the controversy and gave a more exact translation. The Spanish version indeed reads: “...y Dios quizá permitió la servidumbre y trabajo de estas gentes...” (... and God may have has doomed those poor wretches to servitude...). Quizá means ‘maybe’, and not ‘certainly’ as Fumée translated it. This is but a nuance, indeed; but the curse of Ham was a serious matter. After the flood, Ham happened to see his drunken father Noah naked, and he made fun of him. Noah sobered up, and he was in a bad mood. He cursed his son and his son’s son, Canaan: “Cursed be Canaan! A servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren.” (Genesis, 9:25). Those in favour of slavery used this curse as an argument. Was it right in God’s sight for Christians to enslave and even slaughter other men, be they pagans? Was violence a legitimate tool of conversion? Yes—if the Native Americans were Ham’s descendants. It was their fate, as decreed by God; and if God is with us, quis contra nos? The same curse was also used to justify the enslavement of the Africans. They were pagans as well, and slavery was the way God had chosen to deliver them from the wicked hands of the Muslims in order to rock them in the bosom of Abraham. Thus, Gomara was clearly exonerating his compatriots—or was it Fumée? Let’s say that the French translator turned a dubious interrogation into a straight affirmation.

Let’s talk about Noah and his three sons, if you don’t mind—Shem, Japheth and Ham. The Bible says that they were the only humans who survived the flood—with their families. It means that they are the common male ancestors of all mankind. We know that they went to live in their respective territories: Shem’s descendants to the Middle East, Japheth’s to Europe and Ham’s to Africa. What about the Native Americans, then? And this vast and highly populated continent? How come God remained silent about that? The religious soon came up with an explanation: they were also Ham’s descendants, who had been scattered to the ends of the world—serves them right! But why doesn’t the Bible clearly mention them? Could the good old book fail to mention such a tremendous part of the world? What was at stake was nothing less than the infallibility of the Bible! Challenging such a pillar of the Western civilization was one of the most formidable repercussions of Columbus’ discovery. That didn’t prevent mankind from doing evil in the name of righteousness, of course—but although it took centuries, old ‘certainties’ were eventually turned into ‘maybes’. Isn’t it the beginning of wisdom?

This is a 450 year-old book, and it remains an inevitable read to whosoever is interested in the history of America—and the study of mankind. Was Gomara a partial author? Quiza. Is his book an absolute must-read? Most certainly.

Thibault Ehrengardt