Thouvenin Jeune, Younger is no Better

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

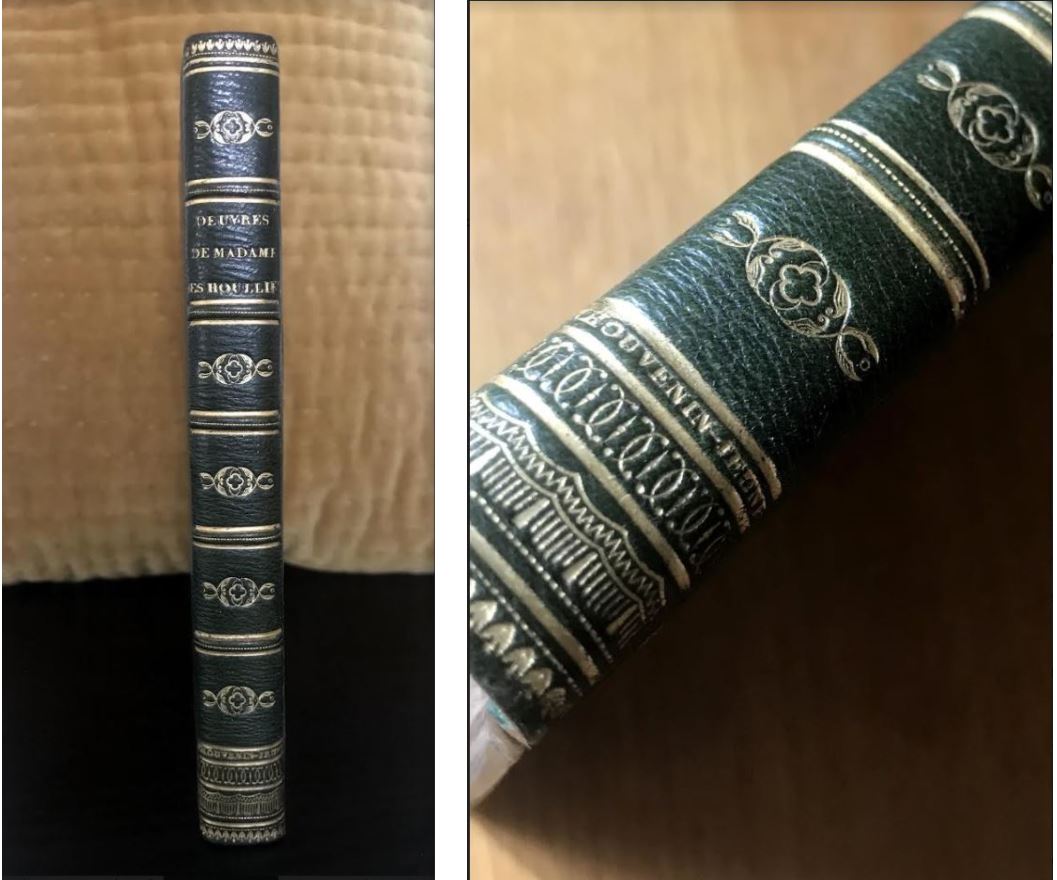

So close and yet so far! was my cry of disillusion when I read “Jeune” after “Thouvenin—” on the binding of a book I had just received from Germany. Well, I was still very pleased with my purchase, as the bookseller hadn’t even mentioned that it came in a signed binding! Nor did he take it into consideration as far as the price is concerned. So, all right—this is not a Thouvenin’s binding but a Thouvenin Jeune’s—less valuable, then; but far less common too.

“Thouvenin! Joseph Thouvenin the Older, the great, the famous student of Bozérian the Younger,” Henri Béraldi writes in La Reliure du XIXe siècle (Paris, 1895). “Thouvenin! One of the most famous names in bookbinding. For his contemporaries, he was a kind of half-God, even a God!” All book lovers know of Thouvenin—his bindings will make a book price skyrocket, and some people buy “a Thouvenin” like others buy “a Voltaire”. This renowned man owes a lot to Charles Nodier (1780-1844), a writer and a publisher who, “encouraged and directed the restorers of the art of binding like Bradel, Niedrée or Bouzonnet and the great Thouvenin, who, as he was dying from a chest pain, sprung a last time from his bed to inspect the bindings ordered by Nodier,” Techner writes in Bulletin du Bibliophile. Among many other things, Nodier and Thouvenin made “fanfare” bindings fashionable again. Reading this name on a book is always an exciting moment! Especially when you didn’t expect it. My book is a 1795 edition of Madame Deshoulières’ poems, and I was stricken at once by the overall quality of the binding. And the pictures the bookseller had provided me with didn’t give it justice—so, I took a closer look at it until I eventually found the name written in very small letters between two golden lines. I was overwhelmed with joy for a second, and then my eyes kept on reading, “Jeune”. Poor me! There were more than one Thouvenin.

The catalogue published by Société de la reliure originale in 1953 reads: “Several members of the family worked in Paris as book binders: Joseph Thouvenin the Older, from 1813 to 1834; Joseph Thouvenin jeune (the Younger), brother of the latter, from 1822 to 1844; then a third brother, François Thouvenin, who died in 1832, also worked as a book binder, but we know of no work of his*.” Many things have been written about Thouvenin the Older—we know that his shop received 3,000 orders every year, for instance. But there’s hardly any information available on Thouvenin Jeune, and even the author of La Reliure romantique (Blaizot, 1987), Roger Devauchelle, doesn’t tell much about him. In 2009 a French bibliophilist named Hugues Ouvrard wrote a short article about Thouvenin Jeune on his Blog du bibliophile. It is entitled The Other Thouvenin. According to him, Joseph Thouvenin’s shop was located at 34 Rue Mazarine, in Paris—Béraldi gives another address, 2 rue de la Parcheminerie. Ouvrard writes: “At the exhibition of the industrial products from the Seine region, in 1823, he (Thouvenin Jeune) displayed ‘several bindings in the same vein as his brother’s’, but ‘the particular care he put in his work attracted the attention of the jury.’ And he obtained an honourable mention (whereas his brother got the silver medal).”

* One has been identified, since. It is a copy of The Iliad (Paris, 1830).

Thouvenin Jeune’s bindings are very nice and neat; they (almost) match the quality of his brother’s. Ouvrard notes that Thouvenin Jeune used the same gilding irons as his brother on a few bindings. “Was the Older lending him his material, or would the Younger call upon his brother for the gilding?” he wonders. This is just another question that remains without answer.

“Thouvenin Jeune’s bindings,” a bookseller wrote on the Internet, “are as nice as Thouvenin’s, but they are rarer!” You can tell you deal with top quality stuff at first sight, indeed. A few of his bindings are currently available on the Internet: Gilbert’s Works bound in a full gorgeous morocco (€600), Imitiation of Jesus Christ (1823), in full red morocco (€50, but it is in poor condition) or a copy of Salluste (1744) in full blue morocco (€550). But they are few. Ouvrard confirms: “(His signature) only appears on one of the 574 books listed on the catalogue of the Descamps-Scive sale (second part, 1925) dedicated to romantic books. In the same catalogue, we find 32 bindings signed by Vogal, 35 signed by Thouvenin (the Older) and 37 by Simier.” They might be even rarer than that: “Thouvenin the Older’s brother, Thouvenin Jeune, had a son, who was also a bookbinder,” Béraldi states. “He was located Rue Godot-de-Mauroi (Paris), and he also signed his bindings Thouvenin Jeune.” Some of the rare known bindings of Thouvenin Jeune might actually come from his son then!

We know that Thouvenin Jeune died in 1844, then years after his brother. “In 1832,” Ouvrard states, “he registered a patent of invention for the use of binding processes applied to frames.” But that didn’t lead him very far, apparently. There’s a French saying that says nothing grows in the shadow of big oaks—and Thouvenin the Older was a gigantic one! Notwithstanding the quality of his bindings, this Joseph Thouvenin will forever be but the Younger.

Thibault Ehrengardt

Link to Ouvrard’s article:

bibliophilie.com/un-relieur-joseph-thouvenin-jeune-lautre-thouvenin