Chaumaix, or the Power of Wit

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

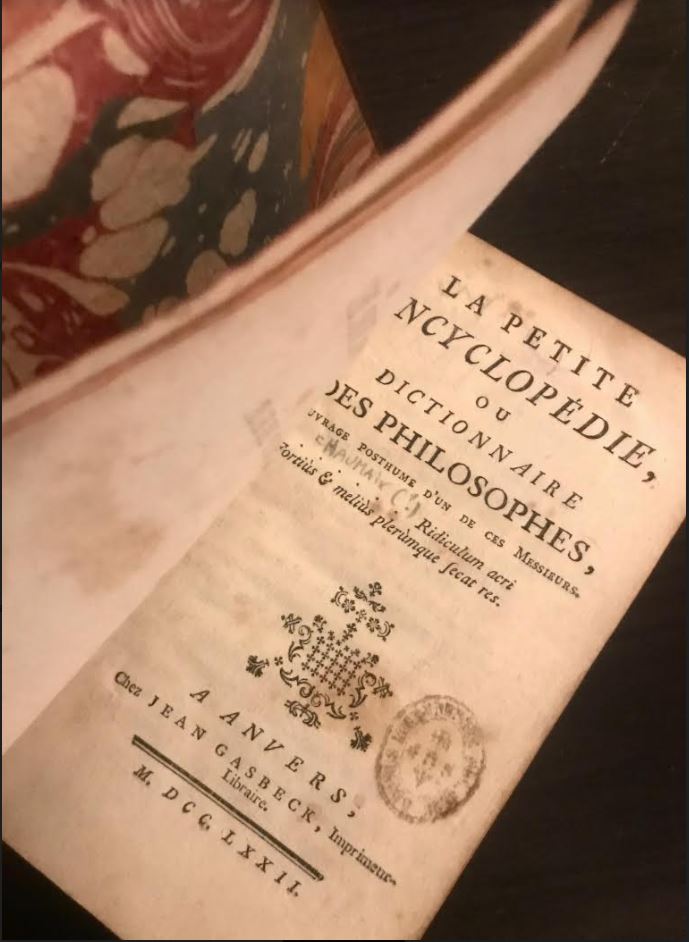

The 18th century will always be remembered as the century of Philosophy. Many conservative writers opposed it at the time by underlining some “philosophical absurdities”. But at the end of the day, they went unheard; partly because of their lack of wit—or esprit. Thus I was surprised to come across a little anti-philosophical book full of wit and humour. It is entitled La Petite Encyclopédie—The Small Encyclopedia (Anvers, 1772), and it is attributed to Abraham-Joseph de Chaumaix (1725-1773).

Wit played a key role in the triumph of Philosophy—Voltaire used, and even abused it at times. After underlining a few inconsistent details from the Genesis regarding the creation of the world, he cunningly concludes: “I guess God sent us the Bible so we would become better Christians, and no better geologists”—this is what boxers call a liver kick. Even when he was wrong, Voltaire was brilliant, and as he once put it: “We forgive everything to those who have talent.” On the contrary, most anti-philosophers authors were devoid of humour. Standing as the defenders of the Faith, they took themselves seriously. Consequently, they were often boring—and who wants to listen to a boring speaker? Notwithstanding, I must confess that I have developed a sort of fascination for anti-philosophical writings. Two hundred and fifty years later, they tell us half of the story that is hardly told nowadays. Plus, their point of view is so radical that they make me laugh in retrospect. Yet, Chaumaix was different—he knew the power of wit, as shown by the epigraph of La Petite Encyclopédie: Ridicule more often settles things more thoroughly and better than acrimony (Horace, Satires). He probably didn’t like Voltaire’s writings, but he shared with him a certain “esprit”.

In 1752, Voltaire wrote to D’Alembert regarding the famous Encyclopédie (Paris, 1751-1772): “You are working on a project that will make your country glorious and put those who persecute you to shame.” As often, Voltaire was right—but Chaumaix disagreed, and he published Préjugés légitimes contre l’Encyclopédie—Legitimate Criticism of the Encyclopedia in 1753. Yet, when our small book came out in 1772, Chaumaix had long left the country to join the more welcoming Court of Catherine II, in Russia. Thus, La Petite Encyclopédie, said to be a compilation of his first work, is only “attributed” to Chaumaix. It is a thin book: “The circumference of our ideas is very limited,” the short preface reads. “Furthermore, isn’t the multitude of terms responsible for all the mistakes in the world? Therefore, my dictionary shall be very short.” Praising the Encyclopédie as the pride of learnt people, and his own work as the delight of true wise men, Chaumaix then explains: “I’ve borrowed from this piece of work the method of using references to other entries to link various ideas.” Giving the definition of BEAUTY, he writes: “The reign of beauty and love has nowadays become the reign of virtue (...). Ô mankind! You shall cherish your benefactors, who made virtue so easy, and pleasant. SEE Love, Concubine, Adultery, Women, Libertinage, etc.” Noticing that some philosophers considered that animals were almost equal to man, he says: “It would be very pretentious to think that animals will never become greater philosophers than we are—(...) their only problems being that they have hooves instead of hands, (...) and that they do not know boredom.” He quotes another philosopher, La Méttrie: “Animals were formed from an eternal germ, no matter which one; and by mixing among themselves again and again, they’ve eventually given birth to this wonderful monster we call Man.” Chaumaix is ecstatic: “Thus, animals are our forefathers—and we owe them respect. This also explains the various inclinations of men: some are closer to donkeys, others to monkeys, lions or magpies. Philosophers being all of them at once.”

When Chaumaix gives his definition of APOSTROPHE, we can’t help laughing. “This is what makes our philosophers so eloquent. When I hear them shout: “Ô men! Ô nature!” I am carried away!” Voltaire would have appreciated. In fact, it reminds us of Marmontel’s style in Les Incas or of certain passages in Raynal’s Histoire des Européens dans les deux Indes... where the author seems to have over the top reactions: “Thinking of some much innocent blood, my eyes shed so many tears that my paper is wet, and—Ô I must stop writing.”

Satires are good only when they are relevant. And Chaumaix had a point to make. At the entry LIBERTY, he writes: “Philosophers who think that pain and pleasure are the two active principles of the moral world; that everything we do in order to avoid pain or to seek pleasure is legitimate; that the laws should preserve personal interest; that probity itself is nothing but the habit of useful actions; that the soul is mortal, and has no duty on earth, and shall suffer no consequences in the afterlife; (...) shouldn’t care so much to know whether they are free or not.” But as I write those lines, Ô reader! Tears of contrition fall from my eyes on my keyboard that starts to bug—and, Ô must stop writing!

* Half-title page, title page, Preface (4pages), 136 pages.