To Fine or Not to Fine – That Is the Question (But What Is the Answer?)

- by Michael Stillman

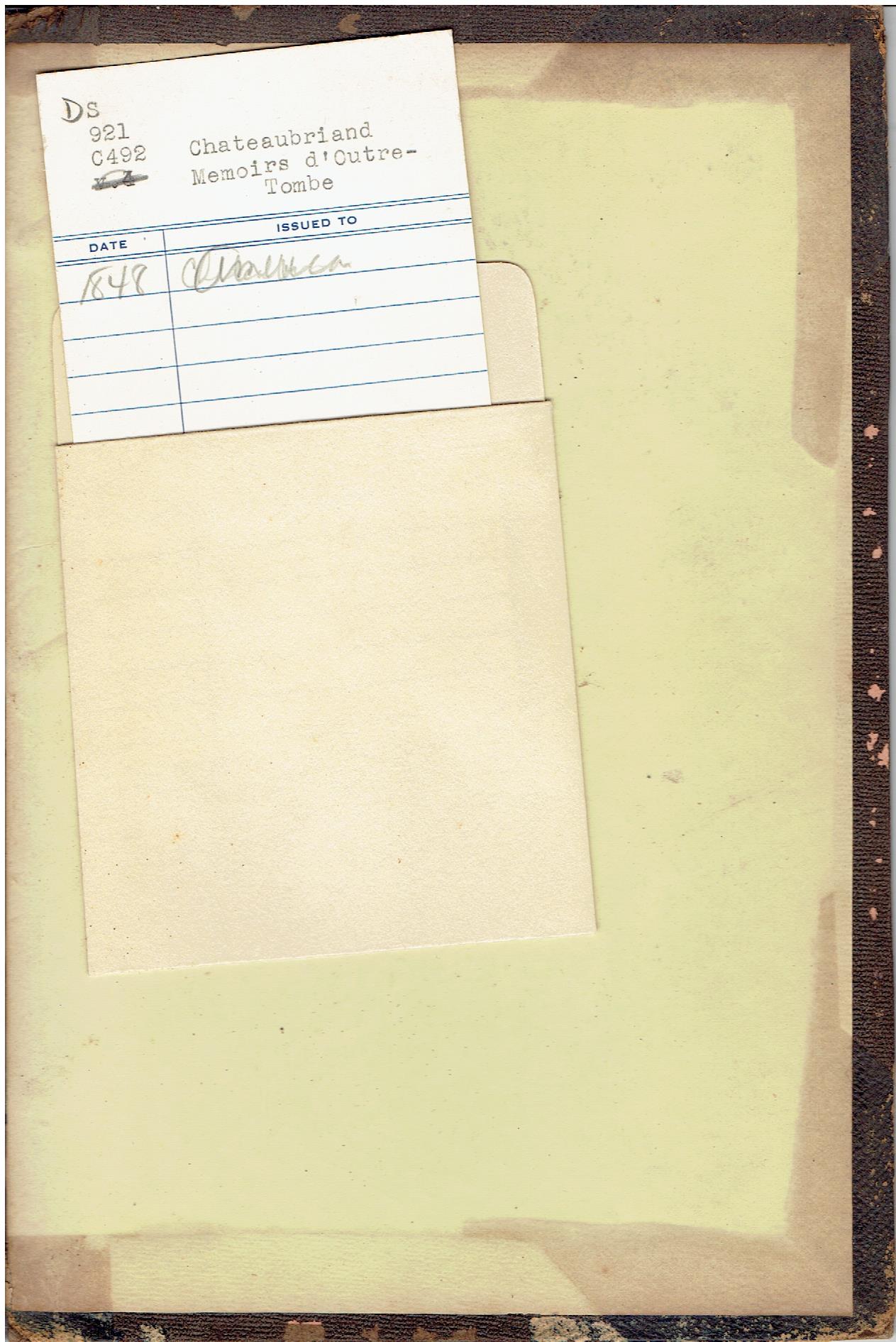

I guess it's time to return this book.

A hallowed tradition of library science could become an endangered species. We are talking about the ubiquitous practice of leveling overdue book fines on borrowers who do not return their books by the required date. To most of our readers, this probably doesn't sound like much of an issue. Most of you have probably paid one of these at sometime or other yourself. Usually the charge is something “nominal,” a buck or two, maybe pocket change. Most of our readers are book collectors, and book collectors are generally middle class people or higher. The fine is inconsequential, the greater punishment being the embarrassment of explaining yourself to a librarian.

However, what an increasing number of libraries have come to realize is that there are many readers for whom these fines are neither nominal nor inconsequential. These are book readers who are poor. For them, the library is even more important than it is for those of more substantial means. They have no other access to books to read. When a book becomes overdue, and they don't have money to pay the fine, they hold on to the book even longer. They are afraid to bring it back, so the fines mount, putting payment of the debt farther out of reach. They never bring the book back. Meanwhile, they are cut off from the library, so they lose all of their access to books. But, people living in poverty also desperately need education to pull themselves out of poverty. Their children need it even more. It is a vicious circle that some can never escape.

Early last year, the American Library Association, recognizing the problem, issued a resolution entitled Resolution on Monetary Library Fines as a Form of Social Inequity. In it, the ALA says “that the charging of fees and levies for information services, including those services utilizing the latest information technology, is discriminatory in publicly supported institutions providing library and information services.” They also point out that library fines take an inordinate amount of staff time imposing and collecting them. The Resolution concluded that the ALA “adds a statement to the Policy Manual that establishes that 'The American Library Association asserts that imposition of monetary library fines creates a barrier to the provision of library and information services.'”

Now, the easy answer might be to say why don't people just return their books on time? The answer is the same as it is for people who can afford to pay the fine. They forget, lose track of the due date, misplace the book, get sick, don't have access to transportation on the right day, or it was borrowed by a child not aware of the requirement. The amount of unpaid late fees on virtually every library's account book attests to the fact this happens to good, honest people all the time.

In the past, libraries have often had amnesties where patrons could return overdue books without incurring a fine. These have regularly returned many books to the shelves the library probably never would have seen again. Indeed, the number of late books typically returned during fine free periods should have been a tip as to the extent of the problem of people not returning books because of the affordability issue. The classic overdue book case was that of Phebe Webb, who borrowed a copy of the ironically titled Forty Minutes Late from the San Francisco Public Library in 1917. She never returned it, but 100 years later, her great-grandson showed up with it during an amnesty period. Based on rates at the time, she owed $2,300. Don't be too harsh on Ms. Webb. According to her great-grandson, she died before the book was due.

As amusing as that story is, here is the more important one. During that fine free period, which San Francisco Public held about once every eight years, 700,000 books were returned. That is a sign of the magnitude of the problem.

Several major and many more smaller library systems have totally removed late fees. Phoenix became the largest city to eliminate fines just a little over a month ago. They will bill patrons a book replacement fee after it goes over 50 days late, but will cancel the bill if the book is returned. San Diego removed fines after discovering they were paying more to collect overdue book fines than they were taking in. Columbus Ohio no longer collects fines and Pittsburgh's Carnegie Library is now testing their elimination in a few branches.

Other libraries have taken in between steps. Some libraries have eliminated fines on books taken out by children. Others have holiday forgiveness programs. Another favorite around holiday time is forgiving fines if the patron brings in an item of canned food to give to the needy. Others now automatically extend the due date for an unreturned book if no one else has reserved it. Several libraries have received recommendations from consultants to remove the fees but have not yet acted.

Still, most libraries have not made the move. The largest public library system in America, New York Public, still collects fines. Then, there is the recent case from Charlotte, Michigan, where a woman was arrested for two overdue books and could have been sentenced to as much as 93 days in jail. Cooler heads prevailed, but she did have to pay the fine.

One thing that large library systems have repeatedly found when undertaking a study of the situation is that the percentage of overdue books, and loss of library privileges, is consistently higher in poorer neighborhoods. This is why the ALA and many libraries have concluded that late fees are discriminatory and erect barriers to those with the least in terms of financial means. For libraries, which struggle to keep their visitor numbers up in these days of e-books and competing forms of entertainment, this is the last thing they need. Money is keeping many potential patrons out just as libraries are fighting to stay relevant. No one wins in a lose-lose situation.

Some are concerned that the lack of fines will result in more books not being returned. However, libraries without fines have not experienced this, and the large number of overdue books returned during temporary amnesties backs up this experience. A temporary loss of library privileges until books are returned, along with assistance for people lacking the necessary fee if a book is lost, provides an alternative that enables people of limited means and their children to continue to have access to what may be their only source of books to read.