Baltasar Gracian, The Art of Prudence

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

Imagine going back in time, and ending up at the Palace of Versailles in the 17th century! Welcome to this golden jungle, populated with fierce courtesans ready to devour you. How will you survive among those terrible people? Don’t worry, just read L’Homme de Cour (The Man of Court) by Baltasar Gracian (1601-1658)! This compilation of 300 maxims is a how-to-make-it-at-Court kit. Let’s stick to it, then.

Our copy was published by François Barbier in Lyon, France, in 1696. The agreement of the King’s attorney, granting Barbier the right to publish this work, is printed on the last page, as “the privilege of six years granted to Jean Boudot on February 25, 1684, is now expired.” The latter is the first French edition. It came out both as a quarto and a duodecimo, adorned with a surprising frontispiece—of the author? No, of Louis XIV, the King of France. The website of the Royal Collection Trust reads: “An engraving of Louis XIV, King of France. Whole length with curled hair, moustache, classical armour, and mantle. The King is pictured seated, holding a book in his right hand and a plan of a fortified city in his left hand, with further maps and plans on a table to the right and with a view of allegorical medals hanging on a wall in the background. The fortified town on the plan held by Louis is Luxembourg, which was captured by the French in 1684 during the War of the Reunions (1683–4). The King is shown seated in a room, with columns and drapery behind and with a view of a garden visible through an open archway to the right.”

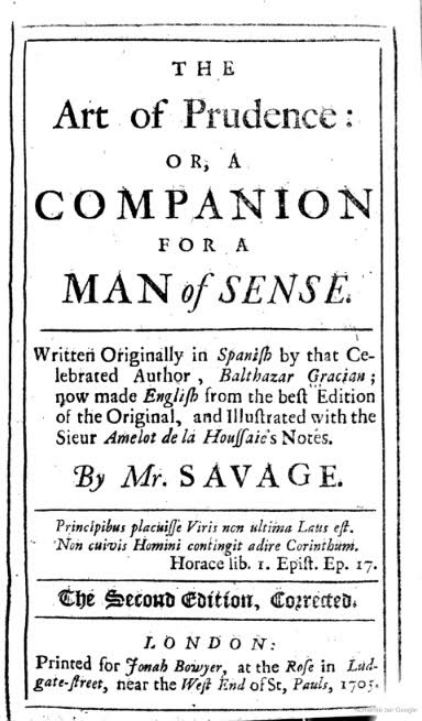

Baltasar Gracian was a Spanish Jesuit. He wrote his maxims in his native tongue, inspired by the Spanish court, and published them under the title of Oraculo Manual y arte de prudencia in 1647. In England, it was later translated under various titles including The Courtiers Manual Oracle or, the Art of Prudence (London, 1685), from which the quotes of the next paragraph are taken. For his part, French translator Hamelot de la Houssaie (1634-1706) “successfully adapted Gracian’s book to the reality of Versailles. Praised for its incisive style and its disenchanted vision of human soul, this treaty soon became the breviary of the courtesans all over Europe,” Joël Cornette writes in 2014 (L’Histoire magazine). In his preface, de La Houssaie explains why he changed the title: “Not only is my title less sumptuous and less hyperbolic than the original, but it is also closer to the contents of the book, which is a sort of rudiment to life at court, or a code of politics.” His epistle to Louis XIV reads: “many maxims faithfully portray Your Majesty.” L'Homme de Cour is very well written*, and full of striking French sonorities that fit the topic and the French ears, as well as the French court.

So, put on your silky socks and your powdered wig, and let’s boldly enter Versailles. Many French poets have described the court of Louis XIV as a cruel and merciless world. Gracian confirms that, whether in Spain or France, “the true wild beasts are where most people are” (maxim LXXIII); but do not panic, with Gracian on our side, we’ll turn predators in this courtesan-eat-courtesan world. First, bear in mind that “there’s neither pleasure nor profit in playing one’s game too openly” (II), and that “we ought then to imitate the method of God Almighty, who always holds men in suspense.” We will stay away from the vulgar—the scum of the earth! Of course, it will be necessary to “speak with the vulgar” (XLIII), because if you “go against the stream”, it is “impossible to succeed.” Thus, we’ll have to adapt our opinions, and learn to “retire within the sanctuary of our silence.”

We are wise, but nobody must notice, for that might be the end of our credit. Let us then “commit small faults on design” (LXXXIII), thus “throwing our cloak before the eyes of envy, to save reputation for ever after.” Let us be “men of metal” and keep a stiff upper lip in any situation, as “a man who is master of himself will soon be of others.” Show some wit to seduce, but don’t you ever, ever “outdo” your master! “Wit is the king of attributes, and by consequent, every offence against it is no less a crime than treason.”

Let’s find the weakness of every man to “gain our ends upon them” (XXVI). Thus we shall be “desired and then regretted” (LIX). Our “conscience” (XCVI) (the French translation says “synderesis”, meaning the highest point of our soul) must tend towards “reason and prudence” as this “natural inclination (...) takes always the surer side.” My dear friends, from near and far (“to have friends is a second being”, but “some are good to be made use of at distance, and others near at hand”), it will be necessary to “comply with the times” (CXX). And always remember that “where there’s no knowledge”, it is “no small piece of wit to counterfeit the ignorant.” Unfortunately, we’re living in an “unhappy age, wherein virtue passes for a stranger, and vice for a current mode!” So, we need to adapt. “Let a wise man live as he can, if he cannot as he would.”

Gracian’s vision of life might be disheartened, yet it is not cynical. Imperfection, when wisely counterfeited, is part of perfection. Moral values are deeply praised in his maxims, but perfect men must act in disguise and “cover themselves with the fox’ skin when they cannot do it with the lion’s,” as “art ought to supply strength.” Yet, Gracian despises deceit and falsehood, as unworthy of “gentlemen.” Like Machiavelli, he is a pragmatic. In Germany, his maxims were translated by Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche considered that “Europe has never produced anything finer or more complicated in matters of moral subtlety.” La Rochefoucauld was clearly inspired by his maxims to write his own, and when a new translation (C. Mauer) of The Art of Prudence was printed in America in 1992, it became a national bestseller. In fact, Gracian’s book was never out fashion, and is still regarded as a masterpiece. First, because it was chiefly inspired by ancient philosophers (Pliny the Younger, Tacitus...), and secondly, because man will be man.

Ironically, Gracian eventually fell into disgrace because of his satirical novel Criticon (1651), published without the approval of his Jesuit superiors. Warned about the discontent of the latter and the courtesans after the first volume came out, the author of “the art of prudence” forgot that “he who yields to his passions stoops from the condition of a man, to that of a beast; whereas he that disguises them, preserves his credit,” and that “he who shows his game, runs the risk of losing it” (XCVIII). He therefore published the second part of his work in 1657, and was soon after exiled to Graus, Spain. Despite all his efforts, and his maxims, he never totally overcame this blow of fate. We can teach wisdom, but can we ever learn?

When Baltasar Gracian exalts “the wise and the prudent” in his maxims, we all assume he implicitly talks about us. Yet, if you often disagree with him, thinking you should always speak your mind, stand for justice notwithstanding the consequences, that you’d rather be “sincere and betrayed” than artful and triumphant, that there’s more to life than success in society, it’s not necessarily because Gracian is wrong. It might be because you—but, shhh! To tell the truth is “to draw out the hearts’ blood.” Thus, “there needs as much skill to know when to tell it, as to know when to conceal it.” Mesdames, Messieurs, suffer that I retire within the sanctuary of my silence.

Thibault Ehrengardt

*La Houssaie also added footnotes taken for other works of Gracian like El heroe, El politico or El discreto.