What Now for the Vast Valmadonna Trust Library?

- by Michael Stillman

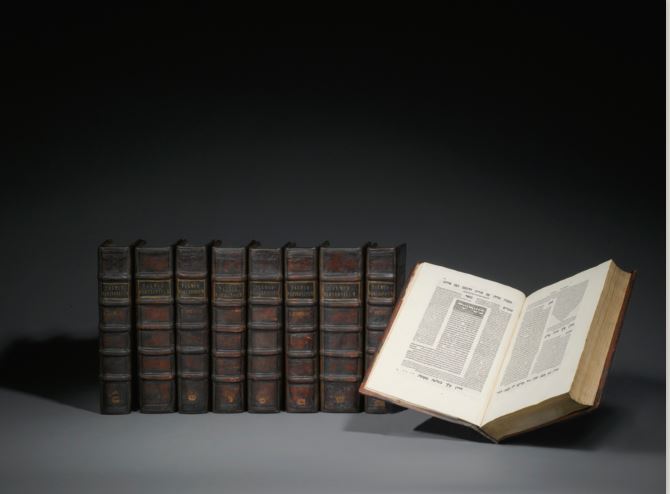

The Babylonian Talmud, courtesy of Sotheby's.

In what could be described as saving the best for last, the most expensive book sold at auction in 2015 was hammered down on December 22 at Sotheby's in New York, the last major sale of the year. That book was a complete Babylonian Talmud, published in Venice by Daniel Bomberg in the early 16th century. It sold for $9,322,000, almost three times the price of the runner up. The second highest priced item, the only known Hebrew Bible published in England prior to the expulsion of the Jews in 1290, sold for $3,610,000. Both of these items were offered at the Sotheby's sale of December 22, one of just 12 items in the sale. The single owner seller was the Valmadonna Trust Library of London. Nine of the 12 items sold, bringing in $14,868,000.

Prior to the sale, the Valmadonna Trust Library owned approximately 13,000 books and 300 manuscripts of Judaica. It was said to be the finest collection of Judaica held in private hands. A quick calculation indicates they still own about 13,291 items. What were sold were clearly some of the finest items from the collection, which leads to the question, what will become of the rest? The trustees aren't saying, but there is an implication there will be more sales. Sotheby's labeled the Valmadonna sale as "Part 1."

The Valmadonna Trust Library began over half a century ago. It is essentially one man's collection. That man is Jack Lunzer, a Belgian born retired British industrial diamond merchant. His wife's family had a small collection of Hebrew books, which fueled Mr. Lunzer's collecting passion. The collection built over the decades, and became something of a solace for Mr. Lunzer after his wife died in 1978.

The collection was placed in a trust by Mr. Lunzer for his five daughters. The trustees operate independently of him, though with obvious concern for his wishes.

A few years ago, with Mr. Lunzer then in his 80's, it was determined plans needed to be made to find a home for his library after he died. However, Mr. Lunzer made a few stipulations. He wanted the collection to be kept together, and to be available to researchers. This created a problem. The library, which before the sale was valued at something in the $40 million range, was too expensive for most of the institutions that are logical buyers to afford. Its size may also have posed obstacles as 13,300 very old items require much space and care.

A few years back, it was reported that the Library of Congress was interested. There were reports that it was willing to pay $20 million, but this is uncertain. The Library never said whether it made an offer. Nothing ever happened, presuming there was an offer, possibly because $20 million was insufficient, or other reasons.

In 2009, the Trust brought the collection to Sotheby's in New York to try to arrange for a private sale. At the time, it was said that $25 million was the minimum bid that would be accepted. Unconfirmed reports said there was a bidder at that price, but the bidder was unwilling to meet the requirements that no part of the library be sold off or that it be made available to scholars. What is clear is that no one was willing to meet all of the requirements of the Trust, including the price. No sale was made.

Today, Mr. Lunzer is 91 years old. It is said that he is no longer able to fully participate in plans for his library. This has made the need to come up with a long range plan more urgent. It appears that his five daughters keeping the collection together is not an option. Unable to sell the collection en bloc, the trustees decided to separately sell some of its most valuable items. It is likely that the two items that headed the list of highest book auction prices for 2015 were the two most valuable. The thought was that if the most expensive items were sold separately, and these nine alone have taken in almost $15 million of the $25-$40 million the trust expects, the remainder of the library could be priced at a figure some institution might be able to afford.

What happens next? Other than the "part 1" implication another sale is coming, it is unclear. Will the Trust attempt to sell off some more top pieces in hopes of further reducing the required price for the bulk of the material? Will another attempt be made to sell the remainder of the collection as a whole, in accordance with Mr. Lunzer's wishes? This is undoubtedly the hope of most Hebrew scholars, but whether such a buyer exists is unknown. Those interested in the outcome of this story, or perhaps even in buying the Valmadonna Trust Library, should keep an eye on Sotheby's upcoming sales.