Abbé Prades, the Little Heretic. Or, Muddy Chaff and Golden Wheat

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

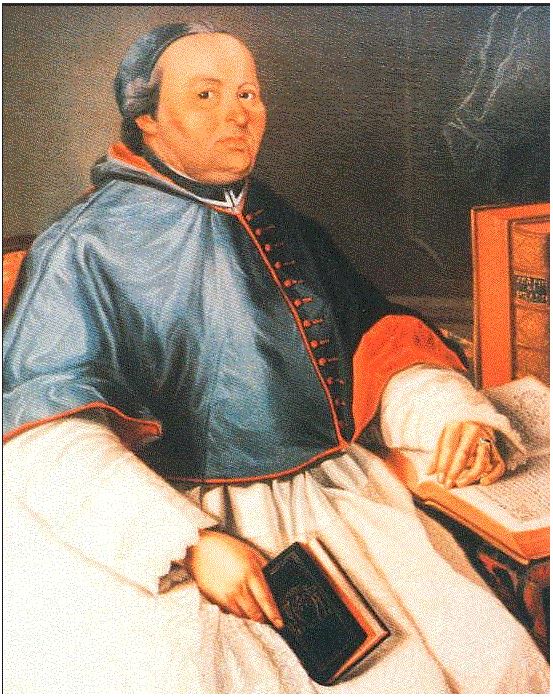

Jean-Martin de Prades.

I love eBay in the summer. Just the other day, I bought a very nice copy of Abbé Fleury's Histoire Ecclésiastique abrégée (Berne, 1767)—a handsome two volumes sets bound in full contemporary calf, Jansenist style—for the price of a regular pack of cigarettes. Who cares about abridged histories? Well—I didn’t intend to invest on the original edition of 1691 (Paris, Chez Jean Mariette), which is a sought after set of twenty in-4° volumes worth a few thousands Euros, but was nevertheless interested in getting a rough idea of what this book, half-despised and half-praised by Voltaire, was all about. I soon realized that this abridged version is a book of its own; in fact, it's an “open philosophical attack” on Christianity—Oh my God!

A Philosophical Preface

Before bidding, I simply read Voltaire’s commentary in Le Siècle de Louis XIV (Khel, 1784): “This Histoire de l’Eglise is the best ever written, and the preliminary discourses are far above the rest; unlike the history, they are almost worthy of a Philosopher.” It was only later on that I came across a more in-depth analysis by the same Voltaire, who clearly used the book as a primary source: “I saw a statue of mud with a few gold nuggets; I kept the gold, and threw away the mud. (...) In the discourses we find some traits of freedom and truth but the main body of work is full of fairy tales an old lady would be ashamed to repeat.” (Mélanges Historiques, Khel, 1784). Though Voltaire referred to the original edition, it was still a good recommendation. When I received the set, I was puzzled by a few details. First, it came out with no “privilège” or “approbation”, two official seals that informed the honest readers that a book could be safely read; and books about religion usually featured both of them. Besides, it wasn’t printed in France but in Berne (Switzerland), a common trick to avoid censorship. The title page also reads: “Translated from English”; yet Abbé Fleury (1640-1723) was French, and he wrote his Histoire ecclésiastique in his native language. In fact, Fleury was the protégé of the famous Bossuet, thanks to whom he became the preceptor of the Conti family; he later on took care of the education of Louis XIV’s son, before being appointed to the Académie française in 1696. Though sometimes suspected of complacency towards Jansenism, he was definitely the kind of author to get a “privilège” for his writings. Notwithstanding, I started to read the forewords, and was caught totally off-guard by the very first paragraph: “In the early days, the foundations of Christianity were like most empire’s, quite weak. A Jewish commoner, whose birth is dubious, who mingled absurdities with the ancient Hebraic prophecies and the precepts of a good moral; to whom were attributed some miracles, and who eventually suffered an ignominious death; such was the hero of this sect. Twelve fanatics then went from the East to Italy, where they convinced many thanks to the holy and sane moral they preached.” I beg your pardon? The fruit of Mary’s womb—dubious? The holy apostles—a bunch of... fanatics? Lord have mercy!

All right—that might have come from an Englishman, after all; a Protestant, trying to belittle the power of the Roman Church. Growing excited, I resumed my reading. Excommunications, anti-popes, and theological schisms; the Fathers of the Church are here described as cunning politicians fighting the kings of the Earth for power rather than sticking to their holy mission. Talking about the Council of Chalcedony, our author wrote: “It would have been difficult for them to add a third entity to the Father and the Son, hadn’t a deceitful and cunning Father found the solution by adding a few lines to the Gospel of St John: In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God.” But, wait! —one of my favourite Biblical quotes, a forgery? “We can also trace back to the same tricking spirit the building of deceitful decrees used as a footstool by the Pontiffs to dictate their will to foreign nations.”

Now convinced that Fleury had little to do with this work, I looked up in Barbier’s Dictionnaire des ouvrages anonymes et pseudonymes (Paris, 1822). It reads: “Translated from English (or rather written by Abbé de Prades, and featuring a preface composed by Frederic II, King of Prussia).” Back to our reading, to the passage dealing with the holy crusades: “To gather some fanatics, the Pope published indulgences; which meant promising impunity to all sorts of crimes for those who would dedicate themselves to the Church and the pontiff. To bring war to Palestine, where there was nothing we could claim, and to conquer the holy land that wasn’t worth the cost of the expedition, many Princes, Kings and Emperors went to expose themselves in a foreign land. In front of their ill concerted expeditions, the successive Popes giggled and rejoiced over the blindness of Man and their own success. During these voluntary exiles (of the Prince and Kings) (...) the Popes despotically ruled Europe. (...) The Church used St Bernard as a tool on several occasions. His eloquence was the perfect poison to feed this epidemic fever; he sent many victims to Palestine, but was too prudent to go himself.” Our author—the King of Prussia if we are to believe Barbier—saw the crusades as the opening of a Pandora’s box: “So many indulgences and pardons for sale created a general loosening of the morals. People grew more and more corrupt; and the Christian moral, once so pure and so sane, was totally put aside; on its ruins prospered external cults and superstition. (...) To put the final touches to this era of vertigo and stupor, let’s add the luxury and splendour of the bishops that were like an insult to the public misery, the scandalous lives and the atrocious crimes of so many Popes, who openly denied the moral of the Gospels and who sold the divine pardons; it all proved that the Church was selling out the holiest part of the Christian doctrine.” And this book was published in 1767 as “A new and corrected edition”, as the original came one year earlier—whoa!

Mr PRADES

Who was Jean-Martin Prades? In his Dictionnaire historique (Liège, 1793), Mr Feller apologized for writing quite a “lengthy” article about him: “I did it because the Thesis of this abbot made history in the revolution currently undergone by Religion.” Prades was a preacher from the countryside, who came to Paris to study theology at La Sorbonne. In 1751, he wrote a thesis that “was approved by the board of the holy university.” (Feller) It was an apology of Christianity, which chastised the incredulous—including Montesquieu; but it was also inspired by the preliminary discourse of D’alembert’s Encypclopédie. As such, it claimed that Man had first lived a life of paganism before being slowly drawn to religion by the development of society. It also stated that emotions were the starting point of human reflection and that the idea of justice was nothing but a reaction of the weak against the oppression of the strong—Prades was close to Diderot, he even wrote some articles in the Encyclopédie. At the time, the Religion was fighting a spiritual war against the philosophers like Voltaire, Diderot or d’Alembert, and every suspicious work was reported. It eventually happened to Prades’. Embarrassed by the burgeoning controversy, La Sorbonne made a fantastic u-turn, and Prades’s thesis was condemned. It was said by Feller to contain “false proposals on the essence of the soul, on the notions of good and evil, (...) on the origins of society, on the law of Nature, and on the revealed Religion (...); but what excited the most resentment was the pagan parallel drawn between the cures of Aesculapius and the miracles of Jesus Christ.”

The Parliament of Paris finally banned this “gross and disgusting” thesis (Feller); so did Benoit XIV. Fearing for his life—at least for his liberty—, Prades left France in a hurry and sought refuge under the wing of Frederic II, King of Prussia, who “gathered beaux-esprits around himjust like the German Princes gather monkeys,” as La Beaumelle put it (Mes Pensées, Belin—1752). “He was Voltaire’s protégé,” wrote Chandon & Delandine (Dictionnaire historique—Lyon, 1804) about Prades, “and as such became the lecturer of Frederic II, who called him my little heretic”. The enlightened monarch, who supported the free thinkers of his time, had a love and hate relationship with Voltaire; the latter actually met Prades in Prussia. He described him to his niece in 1753: “He is, to tell you the truth, the funniest excommunicated heretic ever. He’s gay, amiable and he joyfully endures his misfortune.” The conservative religious of the time suspected Prades to be what he himself suggested St Bernard had been to the Pope, a political tool—in his case, in the hands of the enemies of the Religion. The controversy lasted for a while but Prades eventually signed a retraction in 1754. The Pope reinstituted him, and he died in France in 1782. But just like the Christians had, with their crusades, opened a breech for the Muslims to reach Constantinople—so said Frederic II—, his thesis set a precedent: “Before this, (the Religion) was only attacked under cover, by obscure means and through little underground brochures,” wrote Feller. “The Thesis was the first signal of an open charge. Ever since, impiety, under the mask of philosophy, has been walking in the open, and its partisans haven't been ashamed of writing their names on the frontispieces of the vilest works.”