The Old Booksellers of New York and other papers<br>By William Loring Andrews

- by William Loring Andrews

none

In the year 1828 there came to this busy, bustling, aspiring town, from the wilds of Indiana, one William Gowans,* [NOTE.—The family emigrated to America from Lesmahagon, Scotland, in 1821. They settled for a while in Philadelphia, and then moved to Fredonia, Crawford County, Indiana, traveling by wagon via Pittsburgh.] in search of fame and fortune. He was a youth of twenty-five, a Scotchman by birth, and whilom farmer and flat-boatman on the Mississippi. His experience when "a youth navigating the wild Ohio and the wilder Mississippi" may be given best by the pen picture drawn by himself. "Then there were no byways for boats to escape the rugged falls of the Ohio as there now are. All had to pass through the roaring straits of Scylla and Charybdis. We had, therefore, to plunge over unhesitatingly. Swifter than an arrow from an Indian's bow, or thought, or lightning, or the soul's departure from the body. Not a house stood upon the point of land formed by the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, nor was the land even under cultivation, but in its primitive, wild, dreary solitude. I understand that it is now the site of a large, busy city (Cairo). Seventy miles below, on the west bank of the Mississippi, stood the deserted village of New Madrid, consisting of a few log houses, apparently empty, and the surrounding forest all dead, caused, as I learned, by an earthquake a few years ago. The land at this place sunk ten feet from the effects of the shock, and no doubt the concussion caused these monarchs of the forest to wither and die. Fifty miles still further down stood the [present] city of Memphis. The captain of our sluggish-moving boat landed at this place. I accompanied him up the bank, the river being low at the time, for the purpose of buying a supply of whiskey. The town, I remember, consisted of log houses inhabited by a very poor class of people. After falling down below this town about 50 miles, we met with no settlement until we reached the vicinity of Walnut Hill, now Vicksburgh, the distance being about 600 miles. The only music in the daytime which regaled our senses was the puffing and distressed moaning of the high-pressured steamers which occasionally passed up and down the river, as the case might be, and as an afterpiece, the wild screaming of the numerous flocks of paroquets which travel along the bank of the river after descending to a certain latitude; and in the night, the wolf's wild howl, not on Onolaska's shore, but the banks of the gloomy and solitary Mississippi. The only human beings we fell in with during this descent, which took six weeks, were certain roving, half-civilized whites who had pitched their tents at certain points for the purpose of cutting and preparing fuel for the steamboats passing up and down, and numbers of the native sons of the forest, who could be seen every now and then paddling their light canoes close in to the shore if ascending, and on the contrary, in the centre of the river if downward bound. At first these savage-faced, painted men somewhat alarmed me; but they frequently paid us a visit by coming alongside and on board of our own lazy craft. After becoming somewhat familiar with these grim, black-haired, half-naked fellow-beings, I began rather to like them, and wished for their frequent return to break up our monotony. They left the impression upon me that they were both generous and confiding. A party came on board one day; one of them could speak a little English. He informed us that one of their number was condemned to death for having murdered one of the tribe when intoxicated. We urged him to make his escape, as he appeared to be at liberty. We even offered to take him with us in our boat, but they all declared, as we could understand them, that that would be of no use, for in the event of his non-appearance for execution on the day appointed, his wife or one of his children would have to suffer in his stead. The three great rivers which discharge their heavy contents into the Mississippi—the Arkansas, the Yazoo and the Red rivers—at those points where they lost themselves in the great father of waters, were all solitary, heavy-timbered wildernesses. Not a human being appeared to have disturbed their native wild grandeur. Now I understand that at each and all of these points are busy towns, and likely to become large cities. At this time, according to his biographers, Abraham Lincoln must have been a fellow-boatman with me on these rivers, although I never saw him to my knowledge."

For a twelvemonth after his arrival in New York Mr. Gowans was engaged in a variety of occupations—namely, that of gardener, stevedore, stone-cutter, news-vender and "super" in the old Bowery Theatre. Evidently he was prepared to turn his hand to any honest means of livelihood. But it was not long before he entered on his vocation, for in Longworth's Directory of New York City, 1829 to 1830, we find the name of William Gowan, bookstall, 119 Chatham Street, house 750 Greenwich Street, so by that time he was established, in a humble way, in the business which was to be his lifelong pursuit. Trade in second-hand books, doubtless, was coy and hard to win, and at the outset of his career he was obliged to seek a market for his merchandise by carrying it in a basket to the doors of his customers. In one of his rounds he chanced upon a benevolent Quaker, named Blatchley, who, apparently unsolicited, loaned him the sum of twenty-five dollars. When some time later the young man came to return the money, the considerate old gentleman suggested that he might have further need of this special capital, and that he had better keep it a little longer. His benefactor lived to see him established in, and paid him frequent visits at, his Nassau Street store.

Mr. Gowans informs us that it was largely through the instrumentality of the father of Thomas Cole, the artist, who was a bookseller in a small way, that he himself adopted the profession. He it was who initiated him into the secrets of the secondhand book trade, disclosing his manner and mode of purchase, and the profit he made upon his literary wares.

The bookstall at 119 Chatham Street was simply a row of shelves, protected at night and in the owner's absence during the day on his book-selling peregrinations with wooden shutters, an iron bar and a padlock. It was shortly succeeded by a store at 121 Chatham Street, corner of Pearl. In 1830 he occupied the "Arcade," between John Street and Maiden Lane.

His business ventures must have been attended with a moderate degree of success, for in 1840-41 Mr. Gowans made a visit to Europe, probably not so much on pleasure bent as with an eye to business. He did not find London as attractive as has Mr. Elias Dexter, the old and well-known print and picture dealer, who never has returned to these shores since he left them, twenty years or more ago, on a flying visit to the British metropolis. In a letter from London during his sojourn there Mr. Gowans writes: "All my wanderings and all that I have seen since I left New York have had a tendency to raise America and its institutions in my estimation. I will feel happier in America, should I ever be so fortunate as to return, than ever I have been heretofore. America is the country for a man making his way in the world. In this country, so far as I can see, if you happen to be born among the mud you must remain there."

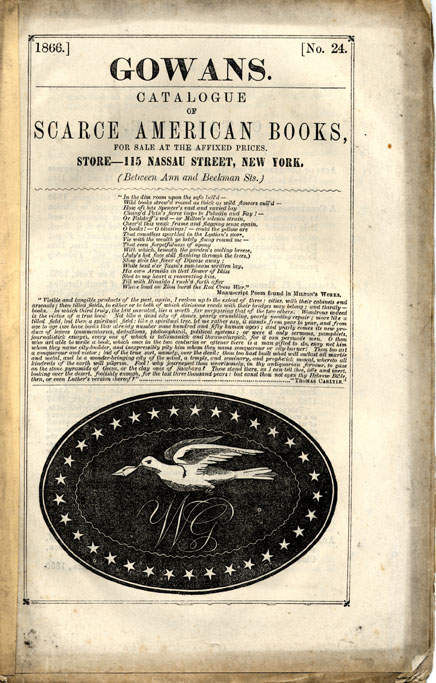

On his return Mr. Gowans devoted his attention for a time to the book auction business, at a place called the Long Room, at 169 Broadway, but soon resumed his second-hand book trade, for in 1842 he was established at 204 Broadway, opposite St. Paul's Chapel, up-stairs. His subsequent locations, as given on the covers of his catalogues, are as follows:

1844--63 Liberty Street, up-stairs.

1848--178 Fulton Street, opposite St. Paul's Churchyard.

1856--81 to 85 Centre Street (Caxton Building).

1863--115 Nassau Street.