Seller Beware: Who really owns it?

- by Susan Halas

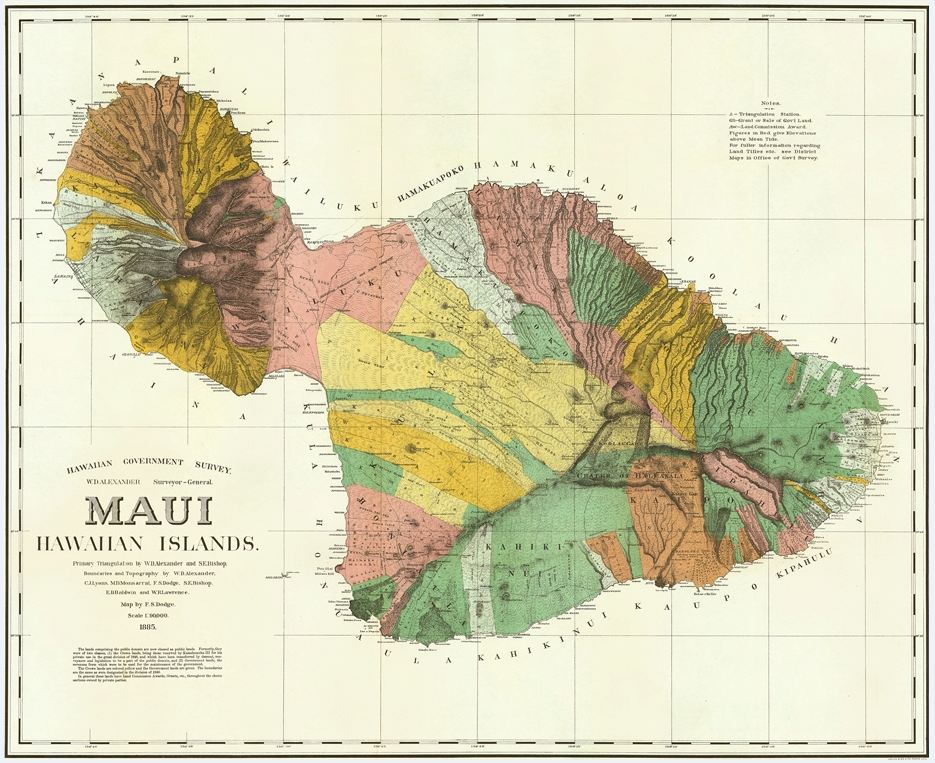

A rare 1885 map of Maui had a gift letter, but it wasn't hers to sell. Photo Fitzpatrick & Moffat.

As a dealer and sometime collector of vintage and antiquarian Hawaiiana since 1979, I’ve run into many interesting collections of books, maps, prints and photos and related antique paper. I’ve bought and sold many of these things and been asked for a professional opinion on many other occasions.

But within the last year two events have made me acutely aware that not everything offered for sale, no matter how authentic, rare or intellectually exciting it may be, is actually the seller’s property to sell.

Beautiful Map Brings a Hefty Price

Incident #1 happened in the fall of 2011. A colleague and I hosted an exhibit tracing the history of Hawaii with a display of maps from Capt. Cook through statehood at a small local museum.

The publicity for the event caught the eye of a local history teacher who had a friend who had an antique map of Maui. The friend asked the teacher if she knew what it was and what it might be worth? The teacher, who had heard about the map show, contacted me. She produced the map and a gift letter.

In brief the letter said that the owner, back on the Mainland, had this map. It had been in his possession a long time, it wasn’t doing him much good and really belonged back in Hawaii. He wanted the teacher’s friend (who was also a friend of his) to have it.

The map was the best copy I had ever seen of the 1885 survey of Maui by WD Alexander. It was in flawless condition. I got chicken skin when I saw it. The hair on my arms literally stood up with excitement.

Though beat up and raggedy copies sometimes came to market in the $200-$500 range, a copy in this shape I said could go for $2,000 to $5,000.

I told the teacher if her friend wanted to sell it I’d be happy to look for a buyer. To my surprise the friend did want to sell it.

I priced it at $5,000, and we agreed on a commission. I took one photo of the map, made a copy of the gift letter and sold it on the first call for the full amount.

A few days later I picked up the check, gave the seller her share. It was smiles all around. That is until a few days later, when early on a Sunday morning my phone rang. Who should be on the other end but the donor and writer of the gift letter, who was nearly hysterical with rage.

Did I not know that he was the archivist at an important American map repository? Was it not crystal clear from his letter that it was his intent to have the map donated to a local school? I’d better get the map back to him and double-quick or he’d call the state attorney general and have me thrown in the calaboose. Did he make himself perfectly clear?

As it turned out, I did get the map back. I reversed the transaction, returned both the map and the letter to the teacher’s friend, who returned them post haste to the irate archivist.

It Was A Wake Up Call

But the experience was a wake up call for me. It made it really clear that the world of libraries and archives and their staffs and the world of dealers and collectors don’t really play by the same rules.

It was clear by the text of the letter that he had gifted the map to his friend, and probably had the authority to do so because as an executive level staffer he had the authority to dispose of or de-accession things that were duplicates or thought to be of minor value.

The map may have been a duplicate, but he was wrong about the value. He found that out when the friend wrote him joyfully about this stroke of good luck and offered him half of the proceeds.

That’s when he panicked big time. He knew that if his employer ever got word of this transaction his career would be toast.

So he changed his story: he didn’t mean to give it to his friend, his letter had been totally misunderstood: he had meant to donate to a school in Hawaii with the friend as an intermediary. Despite the fact that his letter didn’t say anything of the sort, that was his version.

I got him back the map. That left all of us -- seller, buyer and dealer, out the time and the money, but the halls of academe remained serene and nobody was any wiser. It was apparent that Mr. High Mucka-Mucka had a very thin grasp on antique map values in the open market. As for how many other little presents like this he had made over the years from things in his care, who knew?

But now I found out the hard way I had to be more careful, much more careful. I had to really truly thoroughly check on anything I had even the remotest suspicion might come from a library, archive or any kind of public institution. No matter what the letter said, I realized I should have checked with the donor first.