Documents Signed by Historic Personalities from The Raab Collection

Documents Signed by Historic Personalities from The Raab Collection

By Michael Stillman

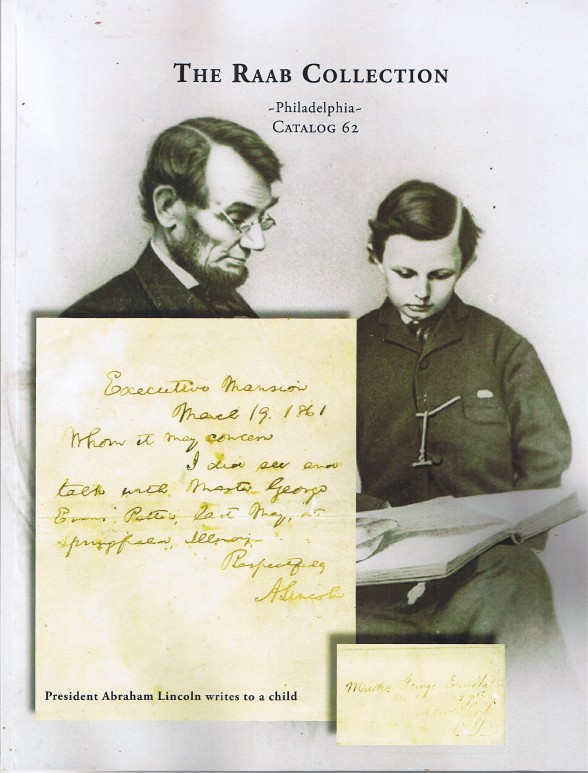

The Raab Collection of Philadelphia has issued their Catalog 62 of documents signed by major, historic figures. Included are both the most important of American names, such as Washington, Lincoln, Franklin Roosevelt, Hancock and Twain, along with those from across the sea, including Churchill, Napoleon, Queen Victoria and Renoir. Many of these documents provide notable insights into the personalities of the signers or the issues of the times. These are some of the important items available in this latest presentation.

Item 18 is a short story written by Mark Twain, a manuscript copy entirely in Twain's hand. In 1885, Twain published perhaps his greatest book, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. He did not publish another major novel until 1889, but in between he helped U.S. Grant prepare his memoirs and wrote some short stories. In 1887, he wrote this seven-page story entitled An Incident. In it, a young boy, with something of a Huck Finn personality, meets Twain on the street. They talk for a while before the boy realizes who Twain is. Finally, the boy asks, "Is it you?" To Twain, this is the ultimate compliment. He notes that he doesn't like exaggerated compliments unless the person does not realize he is exaggerating. Here, the compliment is not faked, but is simply a genuine recognition that Twain is someone of note. Priced at $43,000.

John Hancock's signature became the most famous one in America when he signed it extra large on the Declaration of Independence to make it quite clear to the British exactly how he felt. However, he had cause to use his famous signature before that momentous occasion, and here is one that ties into the reason why he placed it on that document a couple of years later. Here is a bill of exchange for £200 Hancock, a wealthy New England merchant, drew on his London bankers to make a payment on his behalf. It is signed with his famous "John Hancock." However, the London bankers declined to loan him the money to honor the bill, though Hancock was a good customer. They were concerned about repayment as a result of trade problems in America after the Boston Tea Party, and may well have been concerned with Hancock's attitude, which, to say the least, was not pro-British. Item 12. $35,000.

The American success in the Mexican War turned out to be a mixed blessing. It greatly expanded the nation's territory by adding what is today the American Southwest, but at the same time, it increased the hostilities between the North and South. The reason was that the regions were battling over whether the new territories, and eventual states, would be slave or free. The result was that the two major parties, the Democrats and Whigs, began to divide internally along sectional lines, rather than contest between each other. Daniel Webster, the noted speaker and Whig politician who harbored dreams of becoming President, recognized the internal divisions, and fought gamely to hold his party together. In 1850, he wrote a letter to New York attorney and Whig stalwart John K. Porter outlining his fears. He writes, "There have been those who desire to uphold all sorts of local ideas, prejudices, and animosities, by the general strength of the Whig cause. If we cannot free ourselves from these counsels, the Whig Party must inevitably cease to be a great, strong, and conservative party of the country." To this end, Webster would declare himself a "Union man" rather than a northern man, and supported the Compromise of 1850, which enforced the Fugitive Slave Laws that were abhorrent to the North. It didn't work. It just made the once beloved Webster something of a pariah in his home territory, while the Whig Party still broke apart and totally disappeared within a few years. Item 23. $1,800.