Early Printing and Leaf Books from Oak Knoll

Early Printing and Leaf Books from Oak Knoll

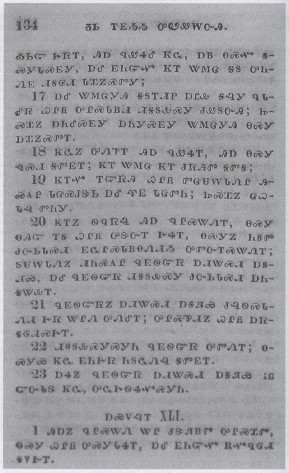

Perhaps the most impressive leaf book you will find is The American Bible, by Michael Zinman, published in 1992. This is a four-volume folio first edition, limited to 100 copies, and printed by the Arion Press. This set provides an account of Bibles printed in America from 1663 to 1878, and includes 38 leaves from these Bibles. Leaves are sorted by subjects: Bibles in native languages, Bibles in English, and Bibles in foreign languages. In the first category, there are leaves from the 1663 "Eliot Indian Bible," the first Bible printed in America, the 1685 second edition of the same, and Bibles in Mohawk, Cherokee, Hawaiian, and other languages. English-language American Bibles include the first such edition from 1782, the first illustrated American Bible from 1791, the first Catholic Bible (1790), Noah Webster's modernized Bible (1883), and the first publication of the New Testament in the Confederacy (1862). Among the foreign Bibles are leaves from the first German language American Bible (1743), the first on paper manufactured in America (1763), as well as Bibles in Spanish, French, Hebrew, Greek, Swedish, and Portuguese. Author Zinman is a notable Americana collector and these leaves came from Bibles in his collection. Item 60. $6,000.

While most items in this catalogue are about old books, here is one that is itself very old: Epistolae Familiares. This is an item of incunabula, printed in Cologne in 1478. It is a book of correspondence of Enea Silvio Piccolomini (Aeneus Sylvius Piccolomini). Piccolomini was born in Italy in 1405, the first of 18 children of a financially strapped nobleman (who wouldn't be with 18 children). He began his career as a teacher and writer, writing romantic and somewhat racy works. His early life has been called "frivolous," somewhat evidenced by at least two illegitimate children he fathered. However, he would find himself working in secretarial and other roles for various religious and political leaders along the way. It would lead him to support the last antipope, Felix V. One would think moves like this would doom his career, at least with the Catholic Church, but Enea had a knack for flowing with the times, and adjusting his positions accordingly. He would resign his role as Secretary to Felix V and find his way back to supporting Pope Eugene IV. All was forgiven. Meanwhile, he would sign on with Frederick III, the Holy Roman Emperor, and his literary skills would lead to his appointment as imperial poet lauriate. In his role with the Empire, the always diplomatic Enea would help resolve differences between the state and the Church, which led to his being appointed Bishop of Trieste. However, his ultimate triumph, hard to imagine for someone with two illegitimate children and a one-time supporter of the antipope, came in 1458. Enea was selected as Pope, taking the name Pius II. The name was chosen to show that he had changed from the rogue of his youth. It seems that Enea truly did change, and he is remembered as a man of goodwill. If he changed with the times, it appears to reflect real changes in the man, not cynical attempts to advance his career. Perhaps this is why he survived so many faux pas along the way to still rise to the highest level in the Church. As Pope, Pius II tried to disassociate himself with his past, even attempting to suppress some of his earlier romantic works. His major goal as Pope was to drive the Turks from the European continent. However, he was not able to muster sufficient forces to make much headway. In an attempt to stir up more support from the European states, he put himself at the head of a crusade in 1464. Unfortunately, he was already ill. Pius II would die shortly thereafter, attempting to lead a crusade that had no hope of success.