The American Revolution from the William Reese Co.

- by Michael Stillman

The American Revolution from the William Reese Co.

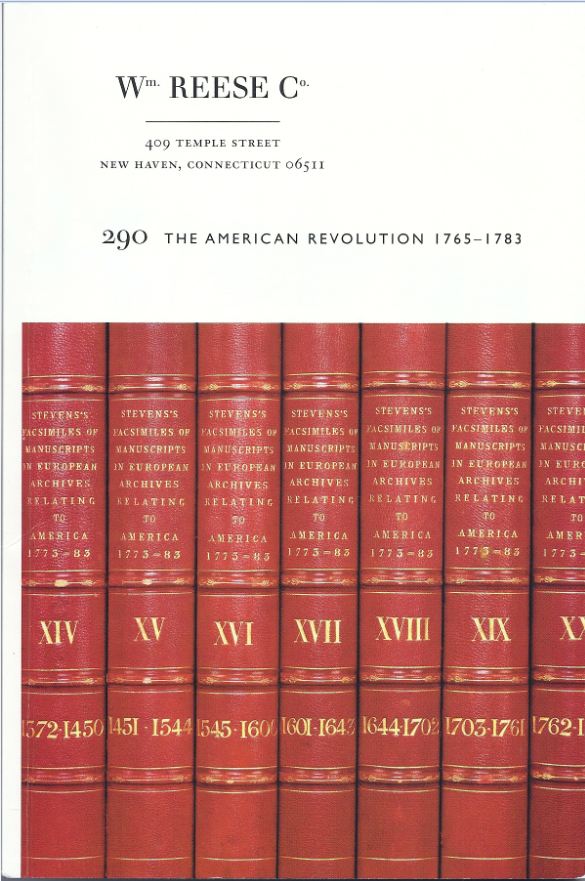

The 290th catalogue from the William Reese Company was recently released. The latest offering from the Americana dealer is entitled The American Revolution 1765-1783. The great majority of items are both about this period and printed within it, though there are a few retrospectives that were published in later years. This was the period during which relations between the American colonists and their British colonial masters quickly broke apart. It would take only a decade of various taxes and other indignities imposed upon the colonists by England to turn resentment into outright rebellion. By the end of this 18 year period, the British gave up and signed the peace treaty that granted the colonies their independence. The United States of America was born. Here are a few items about those momentous years.

The earliest hotbed of revolution was Massachusetts, a place where the British cause was not helped by English governors who had little sympathy for their subjects. No one was less popular than Governor Thomas Hutchinson. He let his opinions of the locals be known in letters he sent back home. Someone, and it is believed that someone was Benjamin Franklin, agent in London for Pennsylvania, leaked the letters. They were published, and not surprisingly, fueled the anger of the colonists even further. Item 80 is the 1774 Dublin edition of The Letters of Governor Hutchinson... It also contains the personal attacks on Franklin made by Alexander Wedderburn, which undoubtedly inflamed American passions even more. Priced at $1,500.

Another Englishman with little more than contempt for the unhappy Americans was Samuel Johnson, the noted lexicographer and wit (Americans probably thought him witless). Johnson should have stuck to writing dictionaries, but in 1775, he veered off into politics and wrote Taxation No Tyranny. Try telling that to Americans! Actually, Americans' complaint back then was not against taxation per se, but against taxation without representation. Johnson wasn't buying it. He notes that Americans claim it is their duty to pay the costs of providing for their safety, but they make this “a duty of uncertain extant, and imperfect obligation, a duty temporary, occasional and elective, of which they reserve to themselves the right of setting the degree, the time, and the duration, of judging when it may be required, and when it has been performed.” To be blunt, Johnson considered the Americans a bunch of freeloaders who simply used lack of representation as an excuse for not paying their way. Item 85. $6,500.

There isn't much Americans like about Benedict Arnold, but a love letter from the nation's most famous traitor is downright creepy. Arnold, a merchant who chaffed under the taxes the British placed on trade, was a vehement opponent of their rule in the years before the Revolution. In 1775, along with Ethan Allen, he led the militia in capturing Fort Ticonderoga. He later served in the unsuccessful attack on Canada, where he was wounded in action. His service was well appreciated by General Washington, but he made enemies of many others along the way. He perennially felt underappreciated and undercompensated, regularly seeking to resign, only to be drawn back to service by Washington. One of his lulls in service came during the winter if 1776-77. He returned to his Connecticut home, but began making regular social visits to Boston. It was there he was smitten by one Betsy Deblois. She was all of 16, while the widower Arnold was 36. He had met her at the home of Boston society woman Lucy Knox. Item 27 is a letter from Arnold to Mrs. Knox, where he asks Mrs. Knox to deliver a trunk of gowns and an enclosed letter to “the heavenly Miss Deblois.” He speaks of the “fond anxiety, the glowing hopes, and chilling fears, that, alternately possess [me].” Lucy Knox did her best to help Arnold, but Betsy had no interest in the dirty old man, finally refusing to answer any more of his letters. Arnold gave up, went on to fight bravely for the Americans at Saratoga, once more felt unappreciated, moved to Philadelphia, married another young lady half his age, and began the process of selling out his country, which ended with his escaping from his command at West Point in 1780 just ahead of capture. He moved to England in 1781, and while also spending time in Canada and the Caribbean, he never returned to America. They would have strung him up had he tried. $15,000.