Devil in the White City by Erik Larson

- by Bruce E. McKinney

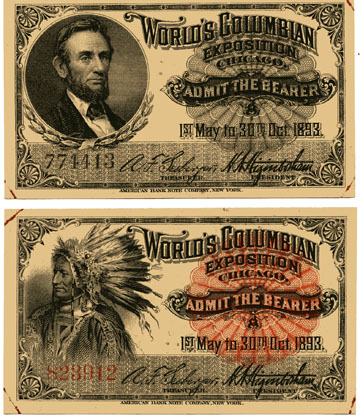

Columbian Exposition tickets reflected American history

A review by Bruce McKinney

In 1893 Chicago hosted the World's Columbian Exposition. To obtain the designation the windy city competed before a national board that considered the applications of four interested venues: Chicago, New York, St. Louis, and Washington. World's fairs had been more or less regular events since the Crystal Palace fair in London in 1851. Philadelphia hosted the Centennial Exhibition in 1876 and Paris the Exposition Universalle in 1889. The Columbian Exposition would honor the 400th anniversary of the landing of Columbus in the New World, highlight the host city and convey the headlong progress and gathering potential of the United States, just then emerging as the foremost world power of the twentieth century. At the same time Dr. Herman W. Mudgett was, like a mantis in a cocoon, stretching his legs in New England and preparing for a new life and identity in Chicago as Henry H. Holmes. In Chicago he would emerge, over a period of years as America's first psychopathic mass murder. His story and the story of the fair are told in alternating chapters.

It is now lost to most people that it was at the Chicago Exposition, at the beginning of the American century, where both the nation and world first peered into the dawning "American era" and saw the future. Many of the seven million visitors who visited during its six months run saw their first artificial lighting, what we know today as electric lights. Those who tasted Cracker Jacks and Shredded Wheat did so for the first time because these treats were introduced here. For many their first glimpse of the just invented Ferris Wheel was the strongest and most lasting impression. America was moving from its agricultural underpinnings toward the industrial power that would define it in the 20th century and the full sense of its burgeoning strength was on display.

That Henry Holmes, a psychopath, would occupy the same time and space was simply the random bad luck that anyone watching television news sees confirmed every few hours somewhere in America or overseas. Where there are people there is mischance and it is only ever a matter of time, never a matter of "if." This book reconstructs the circumstances and events of that mischance in Chicago precisely at the time the Columbian Exposition was being organized, built and run. That the fair somehow provoked Holmes' fantasies of death and sent him into a spasm of continuing murder seems certain although the book never touches on this. Like railroad rails, always together, but never touching, these two stories run side by side. What connections and conclusions may be drawn is left to the reader. In some sense this story telling approach, without conclusions, is the polar opposite of the afternoon television talk shows today that often start with conclusions and present facts and perspectives to lead the viewer to simply accept the host's view.