Google Wins a Small Victory in Long-Running Google Books Case

- by Michael Stillman

A small victory for Google in a long-running case.

Google won a small victory in its eight-year-old Google Books litigation, a lawsuit where the major battles have gone against them. Google has been scanning old books to make their texts available online, reportedly up to 20 million now. Many are very old and clearly in the public domain, but others may or may not be under copyright, and for those that are, locating the copyright holders can be extremely difficult, if not impossible.

When Google began making portions of the texts of these books available, they were sued by the Authors Guild. The Guild demanded permission first be obtained from the copyright holders, even if finding them was virtually impossible. The two sides negotiated for a long time, and eventually reached a settlement. Google would publish only a small “snippet” of the text. If you wanted the rest, you had to buy it. The copyright holders would receive 63% of the payments, Google the other 37%. Authors could opt out or claim their share, and if they did neither, the money would be held in trust for them for a period of time, and then given to charity.

It sounded like a good deal, but many others objected. Some authors did not support the settlement, several of Google's competitors complained, and the heaviest hitter, the U.S. Department of Justice, also objected. Their complaint was that the law requires you must first obtain the copyright holders' permission, and the impossibility of doing so is no excuse. The law is the law. The trial judge, Denny Chin, agreed. Permission of the copyright holder is required, and the Authors Guild, he ruled, has no right to agree to a settlement on behalf of all of the copyright holders who are not members of their organization.

With that, it was back to square one. The Authors Guild reinstituted their suit against Google. This time, they also filed to represent a class action suit for damages on behalf of all of the copyright holders. The first step to such an action is to get the court to recognize the class. Judge Chin recognized them. He noted that requiring each copyright holder to sue individually would be far more costly, and risked having conflicting outcomes from the same set of circumstances.

Google appealed. It cited two major objections. Reminiscent of the claim that prevented the Authors Guild from settling on behalf of the copyright holders, Google said that the Guild could not represent the class of copyright holders as “many members of the class, perhaps even a majority,” approve of Google Books. After all, it does provide a potential source of income from old books, long out of print, unlikely otherwise to ever raise another dime for their authors. Google's second objection was on the “fair use” doctrine. This is a rule which allows you to use a limited amount of copyrighted material. For example, a book reviewer can't reprint or post online an entire copyrighted book, but he can post a few quotes from it. That is what Google believes it is doing in posting a couple of lines, a “snippet,” from the book in response to searches. That, they say, is traditional “fair use.”

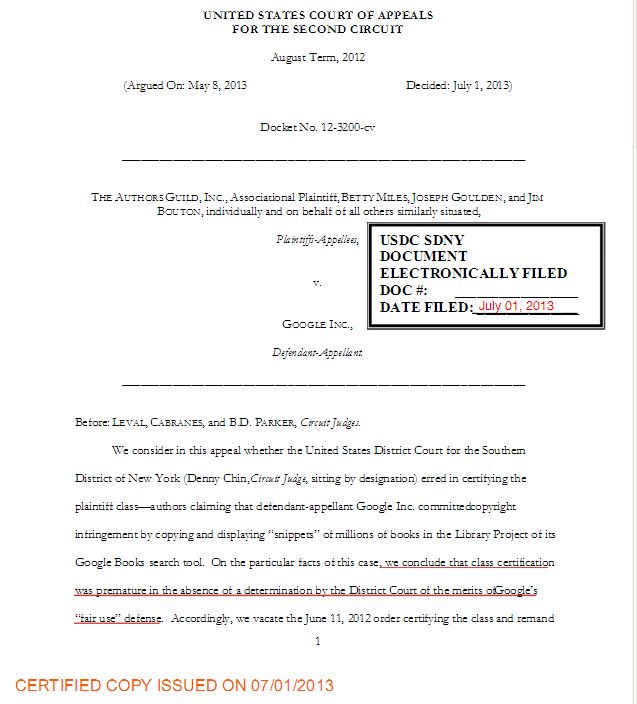

On appeal, the Second Circuit Court did not rule on the first claim, whether the Auction Guild can fairly represent a class action. They did hint that they consider this a serious objection if it ever becomes necessary to decide on these grounds. They described the objections as “an argument which, in our view, may carry some force.” However, they overturned Judge Chin's ruling, at least for the moment, until the “fair use” argument can be decided.

What the Second Circuit concluded was that if it is determined that Google's posting of “snippets” constitutes “fair use,” there is no case for a class action suit for damages. If Google violated no laws, they cannot be sued for damages. So, rather then start an entire class action proceeding before knowing whether a wrong was committed, the appeals court sent the case back to Judge Chin to first decide whether Google had violated any rules, or whether displaying “snippets” from the books was legal “fair use.”

So now Judge Chin must decide whether this is “fair use.” If he finds that it is, this case is over. If he finds it is not, Google will undoubtedly appeal again. Then the appeals court can either overturn Judge Chin again, because it decides that this is “fair use,” or because it finds that the Authors Guild cannot represent a class which includes parties that approve of Google Books, or it can affirm Judge Chin's decision.

It must be noted that while this decision may lead to an end of this class action suit for damages, it will not address the bigger issue – what happens after a viewer sees the “snippet.” Under the earlier, disapproved settlement, the viewer could have purchased access to the rest of the book from Google. Without that settlement, or some other solution, the viewer will not be able to buy access to the rest of the book unless that particular copyright holder has granted Google permission. For all of those “orphan books,” ones whose copyright holders cannot be found, the viewer will not be able to look beyond the “snippet.” If they really want it, they will have to find an old copy for sale or find a library that holds it. They won't be able to click a button and begin reading the rest online.